Energy Education Part 2 Real-World Energy Courses: The Top 10 & Bottom 10 Universities

The Issue

Mark P. Mills

In Part 1 of this Issue Brief on energy education (available here), our survey revealed how the subject of energy is framed in courses for students pursuing degrees in economics, business, political science, law, and engineering at the nation’s top 50 universities. The survey found that 71% of all the courses had a climate-focused learning objective, with just 29% climate-agnostic. The survey also found that no fossil fuel technologies were in a tally of the top 10 energy technologies named across all the courses.

As we noted in Part 1, one might aspire to abandoning petroleum, for example, but the reality is that 95% of the world’s transportation machines use oil. Similarly, one might aspire to seeing wind and solar as the primary source of global electricity, but the reality is that natural gas and coal use are expanding and, together, supply 10-fold more energy than the former combined. Regardless of students’ aspirations, after graduation they will be dealing with the world as it is, not as some may hope.

As a follow-up to Part 1, we partnered again with Professor Shon Hiatt at the University of Southern California to find out which universities offered students the best, and the worst, chance of getting a real-world energy education. We confess that some of the results were surprising.

The Survey

Shon R. Hiatt, PhD

Our survey found 1,425 energy classes among the top 50 U.S. universities; the ranking was based on that of U.S. News & World Report. The goal was to survey those courses intended for students in pursuit of degrees in economics, business, political science, law, and engineering in general. For each energy class, we obtained course descriptions and syllabi in order to understand whether the purpose of the class was focused on giving students a broad understanding of energy markets or whether it was geared toward addressing issues related to climate change. To do this, we employed semantic clustering via BERTopic, an AI natural language processing tool, and extracted keywords related to energy or climate, categorizing similar terms into overarching topics. Climate keywords included targeted searches for specific terms, including “climate change,” “climate justice,” and “energy transition.” Each course was then classified as either “climate-focused” (oriented toward solving climate problems and lowering carbon emissions) or “climate-agnostic” (focused on understanding energy systems, policy, markets, or technologies more broadly), based on the prevalence of the terms. Our prior survey report can be found here, and the entire, detailed collection of syllabi and course descriptions is available here, and the rankings of all universities is here.

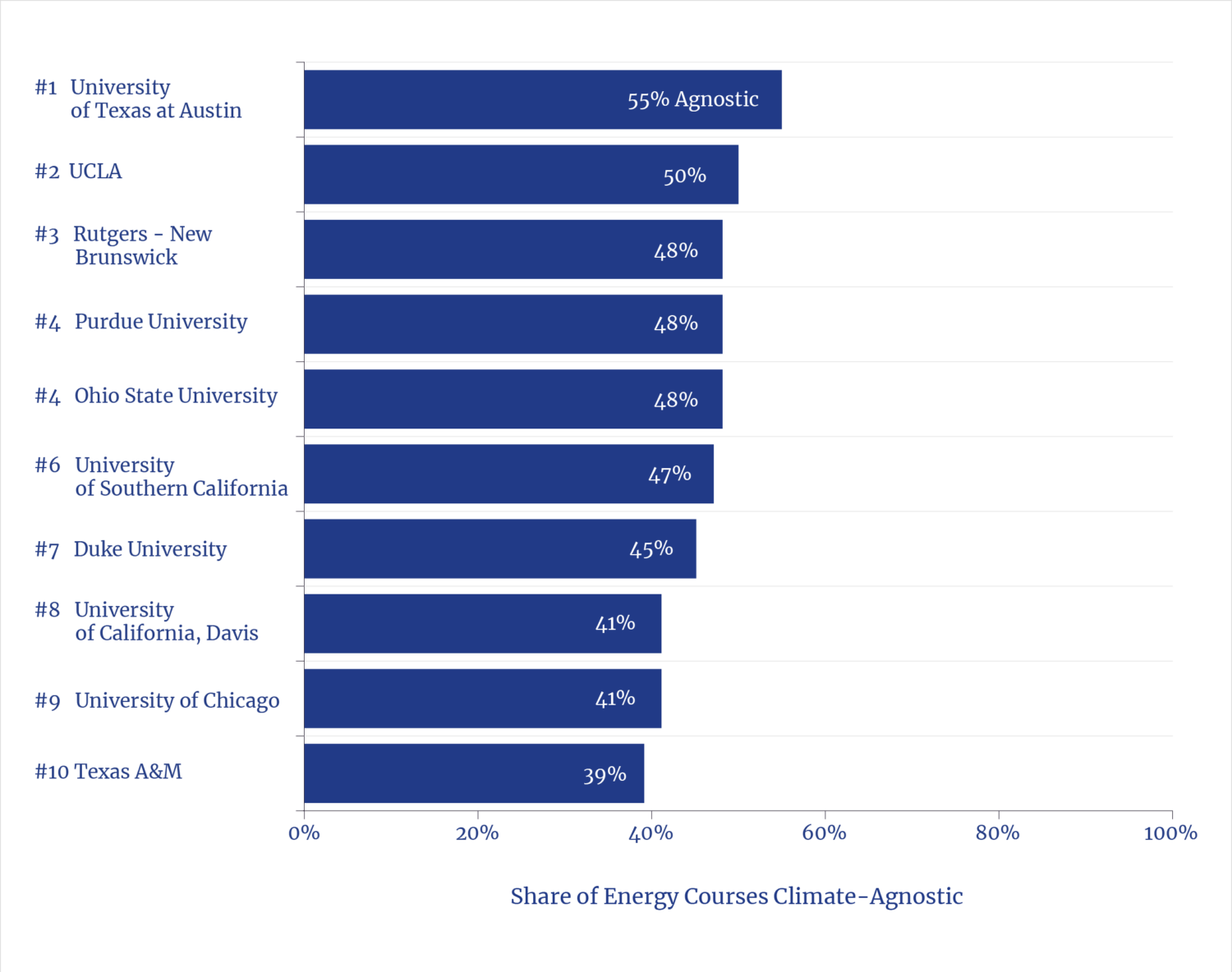

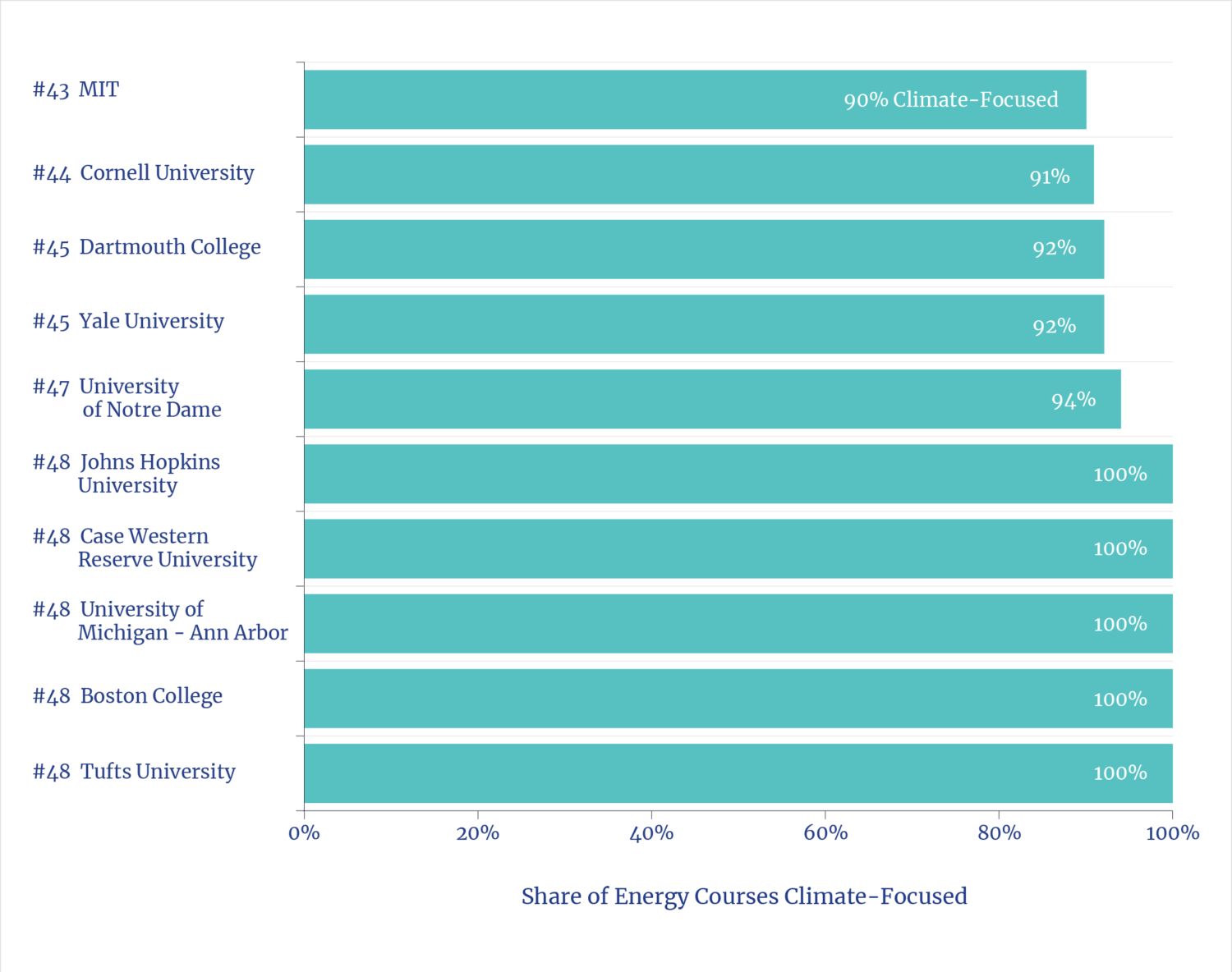

We calculated the proportion of climate-focused versus climate-agnostic classes relative to the total number of energy classes offered at each university. This yielded a percentage breakdown of agnostic-focused and climate-focused classes. We then conducted a rank ordering to identify the top 10 and the bottom 10 universities based on their offering of agnostic, real-world energy classes. Among the top 10 universities (seven public and three private), about half the energy classes offered, ranging from 41% to 55%, were climate-agnostic (Figure 1). In contrast, among the bottom 10 universities (one public and nine private), nearly all energy classes offered, ranging from 89% to 100%, were climate-focused (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Top 10 Universities Climate-Agnostic Energy Curricula: Share of Courses

Figure 2. Bottom 10 Universities Climate-Focused Energy Curricula: Share of Courses

Perspectives

Mark P. Mills

Since the majority of businesses are those that use, rather than produce, energy, most of what will matter day-to-day in the real world has to do with facts about what’s possible versus aspirational. Indeed, understanding energy realities is important even for firms that plan or aspire to avoid using hydrocarbons. Being misinformed about or ignorant of how the energy world operates is a disadvantage, regardless of aspirations.

And as we noted in Part 1, our energy education survey doesn’t reveal exactly what’s being taught. It’s possible that some course descriptions are tilted—“clickbait,” to attract students in ways that don’t reflect course content. Nonetheless, the curricula descriptions are likely indicative of content. That means that many otherwise excellent universities are doing their students a disservice by not offering any opportunity for a foundationally useful, broad energy education.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Shon R. Hiatt, PhD is a professor of business administration at the University of Southern California and director of the USC Marshall Business of Energy Initiative where he leads a multidisciplinary team of faculty, students, and industry partners to advance solutions in global energy with a focus on business value creation through balancing energy security, safety, reliability, affordability, and cleanliness. His research on business strategy, innovation, and entrepreneurship has been published in leading academic journals and featured in popular media outlets. Prior to joining USC, he was a faculty member at Harvard Business School. He received a BA and MPA from Brigham Young University and MS and PhD from Cornell University.

Mark P. Mills is the Executive Director of the National Center for Energy Analytics, a distinguished senior fellow at the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a contributing editor at City Journal, a faculty fellow at Northwestern University’s school of engineering, and co-founding partner in Montrose Lane. His online PragerU videos have been viewed over 10 million times. He is author of The Cloud Revolution: How the Convergence of New Technologies Will Unleash the Next Economic Boom and a Roaring 2020s, (2021). Previous books include Digital Cathedrals: The Information Infrastructure Era, (2020), Work InThe Age Of Robots (2018), and The Bottomless Well, (2005), about which Bill Gates said, “This is the only book I’ve ever seen that really explains energy.” He served as Chairman/CTO of ICx Technologies helping take it public in a 2007 IPO. Mark served in President Reagan’s White House Science Office and, earlier, was an experimental physicist and development engineer in microprocessors and fiber optics, earning several patents. He earned his physics degree from Queen’s University, Canada.