The Choices We Face | Energy for the 21st Century: A Declaration of Guiding Principles

Rationale

Myriad national and local governments are proposing and implementing policies to propel or mandate an “energy transition” to minimise society’s use of fossil fuels. This “transition” idea emerges from, and is driven by, climate policy objectives.

Consequently, debates over energy scenarios, forecasts, and manifestos abound. Notwithstanding the certainties and uncertainties around climate issues, the principles of the physics of energy are independent of climate science. Supplying energy at a global scale requires an understanding of different domains in science, technology, economics, and human nature.

For wealthy nations, concerns about our natural environment—land, water, local air, and atmosphere—have become a driving force behind public perceptions and political goals surrounding energy systems. But we believe that the primacy of human flourishing, globally, is required for all else to succeed.

We believe that civilisation can indeed produce sufficient, affordable energy, and that diversification of the energy portfolio is healthy, but not to the exclusion of fossil fuels—oil, natural gas, and coal—as primary energy sources for decades to come.

Because energy is foundational for civilisation, as a guide for framing civil dialogue and deep thinking around the energy-environment balance, we propose herein nine energy principles, three each in three domains—Economics, Politics, and Science and Technology. These principles are underpinned by the laws of nature, fundamentals of economics, and standards of civil governance, rooted in what history teaches, and what is possible, practical, and reasonable.

While there is much that can and should be debated about details, nuances, and aspirations, we hold these principles to be self-evident . . .

1. Guiding Principles: Economics

1. Lifting up those in poverty to alleviate suffering and promote human dignity requires more energy.

2. Human flourishing requires more energy that is less expensive and more reliable, not less energy that is more expensive and less reliable.

3. In the pursuit of flourishing, humans continually invent new products and services, all of which necessarily use energy.

2. Guiding Principles: Politics

4. Energy security is a top priority for global leaders, revealed in their actions, if not always their words.

5. When wealthy economies export energy production, they impose environmental impacts on less-wealthy nations.

6. Government mandates and/or excessive intrusion in markets stifles energy innovation, options, and freedoms.

3. Guiding Principles: Science and Technology

7. Capturing and delivering energy to society is about inventing, building, and perfecting technologies based on what physics and engineering allow.

8. All society-scale energy systems have environmental trade-offs.

9. The energy available in nature itself is fundamentally unlimited.

Introduction

A global challenge exists today in reconciling the conflict between policies seeking to ensure that society is provided with affordable and reliable energy for everyone, while at the same time protecting the environment everywhere. This challenge is not new. Ever since humans first rubbed sticks together to create fire, early naturalists and philosophers lamented the resulting denuding of great forests in pursuit of fuel for heat. History records ancient scholars decrying the hazards of mining, an industry that dates back thousands of years, in pursuit of the near-magical properties of nature’s basic elements.

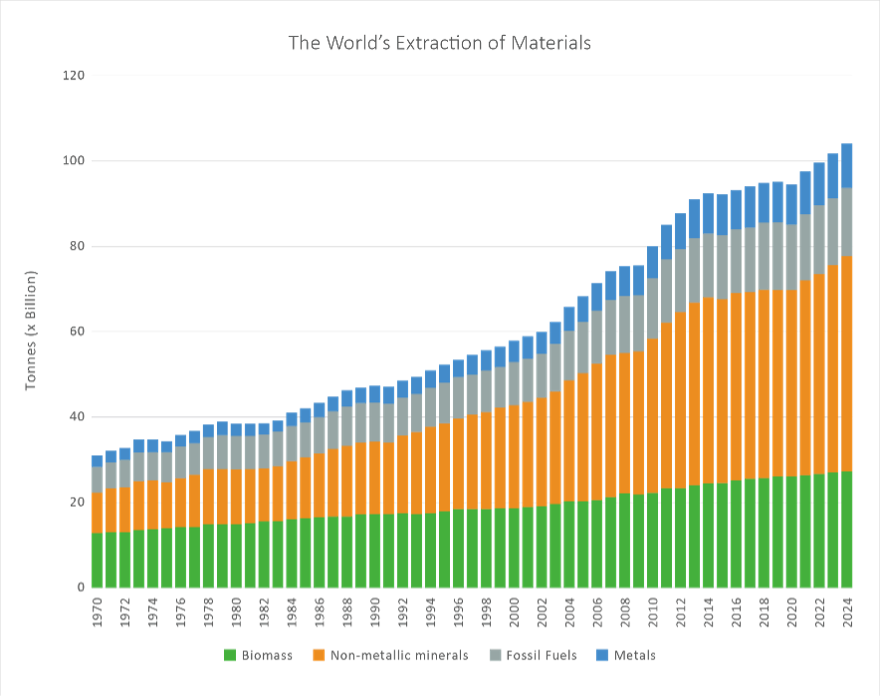

The sheer scale of humanity’s needs today adds urgency to the truism that “quantity has a quality all its own.” To feed, shelter, move, educate, and power civilisation, humanity acquires and uses some 100 billion tons of materials annually (Figure 1). Energy is critical to every aspect of these materials. Can we simultaneously address both challenges—the vast amount of energy needed and the environmental implications at such scale—or must a binary choice be made? The answer is not binary, but based on trade-offs grounded in informed debate over how to reconcile aspirations with realities.

Figure 1: The World’s Extraction of Materials (Billions of Tons per Year)

While debates over the energy-environment balance are a necessary part of framing governmental policies, modern disagreements have too often devolved into a cartoonish political framing, wherein one side is seen as pursuing energy security regardless of environmental impacts, and the other pursuing environmental metrics, especially now climate-related, regardless of costs. But the political and social reality is that solutions that reasonably meet the needs of most people cannot satisfy the full ambitions of extreme partisans. Attempts to do so predictably fail.

In terms of meeting society’s energy needs, physics and economics guide what is possible, and both are largely independent of the environment. The challenge of providing yet more energy is locked into the reality that, barring some unforeseen, catastrophic natural or human-caused disaster, the global population will continue to grow for many decades, especially in low-income, emerging nations. Today oil, coal, and natural gas meet over 80% of all global energy demands.2 Although that percentage is down from over 90% 60 years ago, in that same timeframe, the absolute consumption of fossil fuels has increased nearly 350% because of greater overall energy demand.3 Today, the remaining 18% of energy comes from—in decreasing order—hydropower, nuclear, biomass, wind, and solar. More of all these sources will be needed if we are to meet future energy demands.

Many emerging nations hope to improve economically, with rising energy use per capita accordingly. “Roadmaps” in pursuit of Net Zero Emissions are anchored in goals to rapidly reduce the use of fossil fuels, most notably those from the International Energy Agency (“IEA”), which proposes a decline in total global energy use, while acknowledging that the world’s economy and population will inevitably increase. Some net-zero proponents go so far as to suggest that citizens should accept a new definition of “growth” that is decoupled from gains in economic prosperity.4 However, history and reality suggest a desire for economic growth everywhere which, invariably, leads to the need more energy, not less.

Plans to supply global energy demand require an understanding of the interdependence of basic principles in three domains: economics, politics, and science and technology.

I. Economics: While all features of energy supply are important, maintaining affordability at scale underpins modern life, and is key to enabling the flourishing of today’s impoverished societies.

1. Lifting up those in poverty to alleviate suffering and promote human dignity requires more energy.

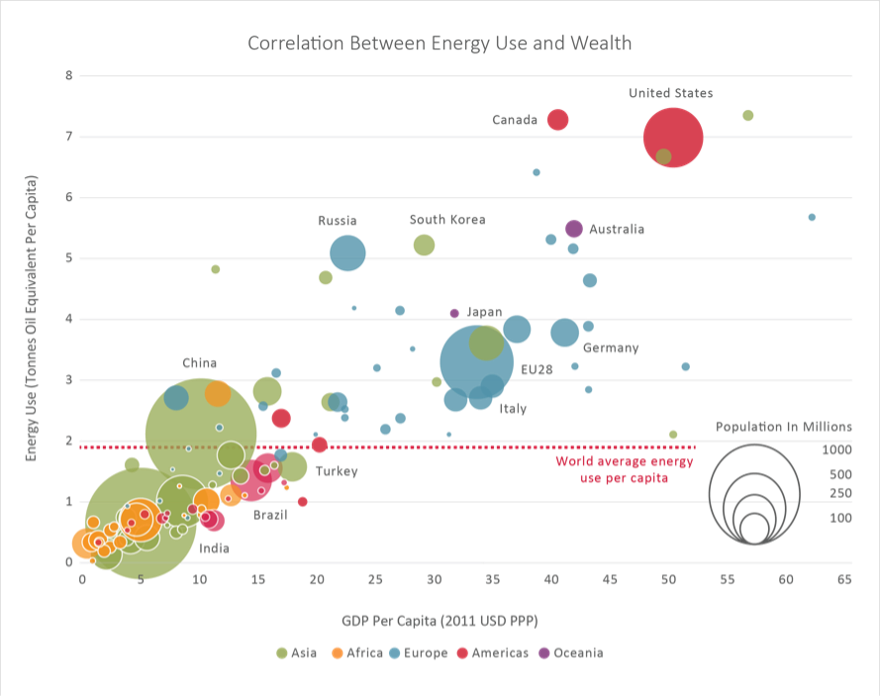

There is a very strong correlation, both historically and globally, between access to affordable, reliable energy, and the realisation of safety, comfort, convenience, and beauty—what we call human flourishing. Yet, globally, there is an enormous spread between the per capita energy consumption in developed nations compared with nations that are developing or yet still emerging. A minimum level of per capita energy use is required for what most would consider a decent quality of life. Some two-thirds of the global population live below that level.

Energy will not end poverty, but we cannot end poverty without energy.5

The globally universal correlation between per capita wealth and per capita energy consumption (Figure 2) highlights civilisation’s core challenge. Approximately two-thirds of the nations in the world fall below what most would consider a reasonable flourishing income. Higher energy costs make products and services more expensive. Income determines a person or family’s ability to purchase goods and services, starting with the basics of food, clothing, and shelter, and evolving to plumbing, heating, and cooling. It also determines access to many things citizens in wealthier nations take for granted, such as cars, education, healthcare, and leisure.

Unsurprisingly, there is a tight correlation between poverty and “deprivation” of the entire range of basic products and services that are taken for granted by wealthier citizens. A personal car is the iconic energy-dependent product that is highly correlated with freedom of mobility, as well as improved personal and national economic outcomes. In the United States, there are roughly 800 cars for every 1,000 people; in poorer nations, there is only few cars for every 1,000 people.6

Anyone with personal experience in energy-impoverished communities has witnessed the transformative impact that access to energy can have on lives, even when it involves only a few light bulbs, ceiling fans, or water pumps. (See, for example, the documentary film Switch On.)7 Even with a standard of living well below that of the wealthy world, people in these emerging and developing economies feel a sense of hope as they look to the future and their lives improve.

Figure 2: Correlation Between Energy Use and Wealth

Much of the rhetoric one hears from representatives of wealthy nations at global gatherings—such as UN-sponsored climate events, and business events such as DAVOS—is focused on the goal of lowering global CO2 emissions. Such a singular focus not only ignores the realities of multidimensional environmental issues, but more importantly ignores energy poverty and the central need for access to a sufficient supply of affordable energy. This is the only way to increase well-being everywhere and reduce destructive global disparity. For the foreseeable future, much of the energy to achieve this will come from oil, natural gas, and coal.

It is time to power the people.

2. Human flourishing requires more energy that is less expensive and more reliable, not less energy that is more expensive and less reliable.

Unreliable energy constitutes a classic economic externality. One can estimate the economic or social cost arising from insufficient energy, or no energy at all, for extended periods. The issue is not merely one of inconvenience or shortage-induced price hikes. There are real if not easily quantified, social, personal, and business costs of doing entirely without the use of some product or service for an extended time. As a practical matter, it is easier to gauge the cost of ensuring reliability in the first place.

Solar and wind are growing faster than all other forms of energy, but that rate is the arithmetical result of growth at any early stage. In absolute terms, solar and wind combined supply less than 6% of global primary energy.8 Some policymakers believe far larger shares of solar and wind are desirable and economical. But given that wind and solar are, by nature, episodic, it is critical to assess real-world costs while ensuring electric grid reliability.

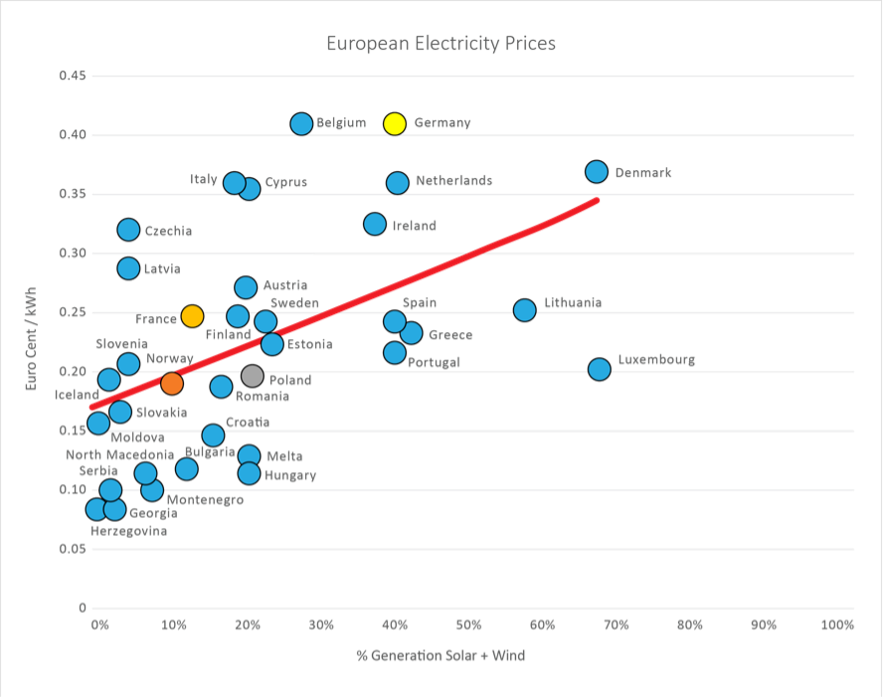

Utility-scale wind and solar require vast areas of land, which makes them inherently more vulnerable to storms and disasters. A more fundamental challenge is converting episodic power to reliable power. Wind and sunlight vary not only with time of day and weather, but also seasonally. To compensate for that, utilities must maintain and operate a conventional grid as backup, and store electricity at society-scales. Either or both of those solutions mean, in effect, utilities need to over-provision grids, which in turn leads to higher capital and operating costs. Reliability is expensive to achieve with episodic power and leads to higher costs to the consumer. That is a significant part of the reason we see, across Europe and in American states such as California, higher average electricity costs associated with higher shares of solar and wind generation. (Figure 3).

At the American national level, about $200 billion dollars of conventional natural gas power plants (so-called “excess” capacity) can provide backup sufficient to deal with weeks of variabilities in weather, disasters, accidents, and maintenance, as well as normal peaks in human behaviours.9 By contrast, it would cost trillions of dollars (assuming future, cheaper prices) for enough batteries to supply a couple of days of grid-scale electricity storage.10 In addition, to charge those batteries when the sun and wind are favourable requires building excess wind and solar capacity beyond normal grid demands. Models based on decades of meteorological data show that to make wind/solar as primary power would require a combination of trillions of dollars in batteries, plus building an overall grid capacity several-fold greater than conventional, which would still be less reliable than today’s grids.11

High-cost electricity tends to drive down economic productivity, because energy is fundamental to manufacturing technology and other critical industrial sectors. We see the result of this trend over the last two decades, where Europe’s economy has grown by about 20%, while the United States has grown by 200%, and China by 500%.12 Although economic growth factors are complex, affordable and reliable electricity in the United States and China is an important underlying driver.

Figure 3: European Electricity Prices

Highlighted: Poland coal-dominated, Norway hydro, France nuclear, Germany solar and wind.

The high price of wind and solar deployed at society-scale illustrates an important cost of supply principle. Because everyone needs reliable energy—whether electricity, gasoline, or heating fuel—the higher the overall costs, the more damaging it is proportionally for those who can least afford it. High-cost energy policies are what economists call regressive. Ironically, some of the most “progressive” energy policies—i.e., incentivising and mandating solar, wind, and batteries, and forcing fossil fuels from the market—result in regressive economic impacts. Governments can subsidise such costs for the most disadvantaged, but such subsidies are unsustainable at society scales. A diverse portfolio of energy options, including primary use of conventional generation, is much healthier to meet the range and scales of demands.

3. In the pursuit of flourishing, humans continually invent new products and services, all of which necessarily use energy.

Economic growth is propelled by imagination and invention. Thus, energy demands are created by the invention of new energy-using technologies that come from the unending pursuit of flourishing, safety, convenience, and beauty. There was, for example, no demand for energy for automobiles before the invention of the car, similarly for digital technologies including artificial intelligence.

To build and power inventions, civilisation needs both electrons and molecules, i.e., kilowatt-hours and fossil fuels. While electricity demand grows faster than the demand for non-electric energy, we cannot, will not, and should not try to electrify everything. Many processes are made possible by the ability of fossil fuels to deliver the extremely high heat required to fabricate cement, steel, and other vital materials, and also as feedstock for many critical materials, not least of which are fertilisers and plastics. The latter, while often vilified, are essential in myriad products, including in medical domains and vehicles of all kinds.

Improving the well-being of the billions who live in poverty will vastly increase the demand for, and thus the energy associated with, all conventional products and services from home heating and cooling, to transportation, healthcare, and more. Then, in wealthy nations there is the further effect on energy demands from continued invention of new kinds of products and services. For example, about $150 million of electricity is consumed over a decade for every $1 billion of electric vehicles (“EVs”) sold.14 Some $300 million in electricity is consumed over a decade for each $1 billion of new semiconductor factories built.15 More than $700 million in electricity is consumed over a decade for every $1 billion of data centres constructed.16 Hundreds of billions of dollars are being deployed annually in the United States and Europe for each of those technologies.

It is precisely because of energy demands for new products and services that even mature economies should expect to see energy consumption continue to grow. In the United States, for example, energy use rose by nearly 300% over the past 75 years, versus a 200% growth in population.17

New energy demands over the past 75 years were satisfied mainly by fossil fuels with hydropower, nuclear, and other options playing lesser but growing roles. While it is reasonable to assume energy demand growth will slow with a slowing rate of global population growth, it remains to be seen whether imagination and technological innovation might continue to fuel a net increase in overall demand.

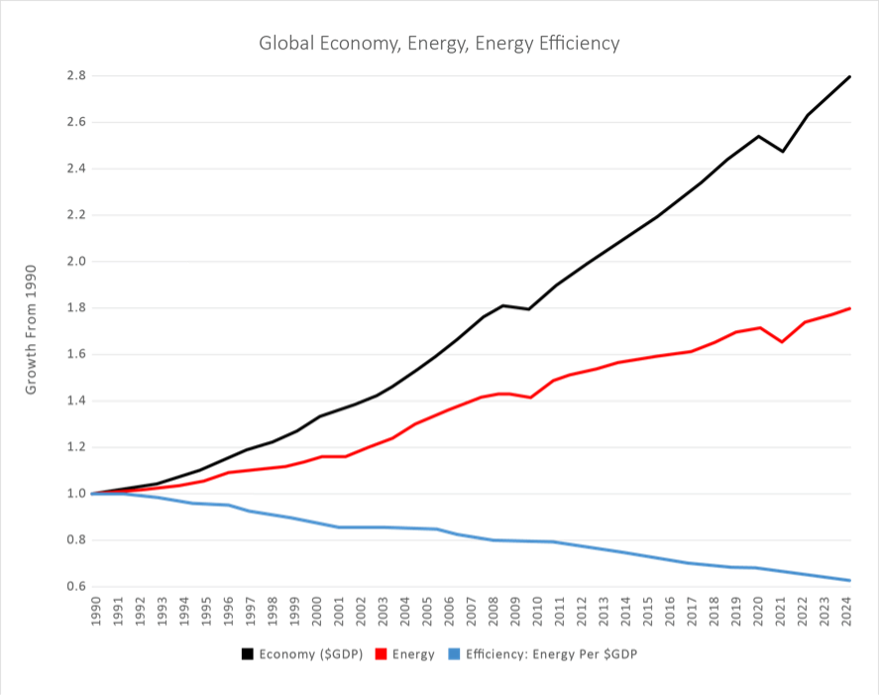

Of course, energy demands can be moderated by conservation and greater efficiency. Choosing to do less—i.e., conserving—is fundamentally a lifestyle choice, but should not be mandated. Meanwhile, efficiency—doing more with less—is helpful so long as the measures are cost-effective, and that proponents understand the associated “paradox.”

Increasing efficiency does not eliminate the need for more energy. In fact, rising efficiency leads to greater energy use, a seeming paradox first identified in 1865 by the English economist William Stanley Jevons. With products or services that people and businesses see as valuable, greater efficiency—fewer inputs of resources, land, or labour to yield the same output—lowers the cost of the output. This in turn stimulates demand. (Figure 4). Making products and services more energy-efficient effectively makes them more affordable and accessible for more people, and thus increases overall energy demand.

Figure 4: Energy Efficiency Drives Growth

Some countries and some American states (e.g., Germany, the United Kingdom, California, and others) are intent on eliminating coal, oil, natural gas, and even nuclear, from their energy portfolios. The resultant energy mix—solar, wind, biofuels, batteries—is less diverse, more expensive, and less reliable than a diverse energy mix. This agenda is fundamentally a lose-lose proposition that stifles innovation-driven growth, impoverishes people, and makes it harder to afford environmental protections, including emissions reductions, among other things.

II. Politics: Governance is inherent to civilisation, and ensuring secure energy supplies is an obligation of civil societies.

4. Energy security is a top priority for global leaders, revealed in their actions, if not always their words.

The planning and practice of ensuring affordable and reliable energy supplies can only be achieved with well-founded inferences about the future. Nations need secure energy, and physically dense forms of energy—nuclear and hydrocarbons—are typically either inherently more secure, or more easily made secure. The means to achieve effective energy security vary tremendously globally. Politicians necessarily set priorities, and actions more than words illustrate the reality that energy security is prioritised over other factors, including climate goals, especially in times of crisis.

The German story is nuanced, but instructive since the nation remains, for now, an industrial and strategic powerhouse; it is the world’s third largest exporter after China and the United States. Beginning in the 1970s, Germany began to consider weaning itself from nuclear energy, motivated by environmental—although, ironically, nuclear has extremely low CO2 emissions—rather than strategic or economic concerns.

In the 1980s, two iconic events altered the political framework: the Russian nuclear accident at Chernobyl and climate change as a policy motivator. Germany subsequently set ambitious CO2 emissions reduction targets and a multi-decade, multi-trillion-dollar solar and wind energy program (Energiewende, i.e., “energy transition”). At the same time, Germany began to phase out nuclear power, and later accelerated that phase-out in response to Japan’s Fukushima reactor accident. Germany’s overall primary energy consumption began to fall from around 2006, and today is about 20% below its peak. Solar and wind surpassed coal as Germany’s leading source of electricity, and the fossil fuel share of total primary energy declined from 84% to about 75% today.19

The trade-offs: Although its CO2 emissions have fallen somewhat, Germany’s economy grew at one-third of the rate of the American economy over the past two decades; its industrial output has dropped precipitously; and it has converted to a net importer of electricity from the European Union (“EU”) after three decades as a major exporter.20 Consumer electricity prices have more than doubled, and most subsidies to protect major industries were reduced or eliminated because they were economically unsustainable.

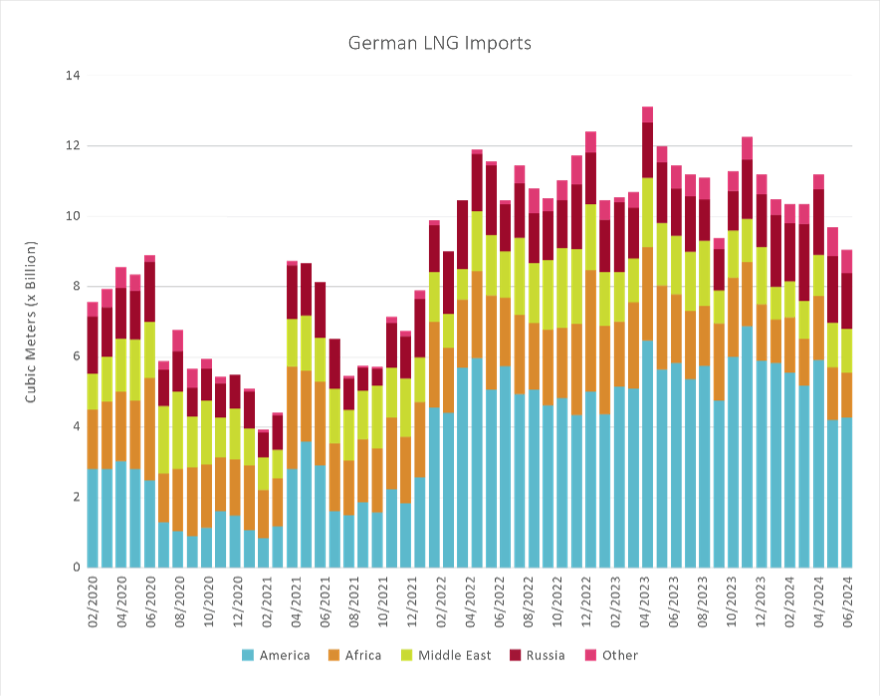

Energiewende ignored energy security implications, made obvious with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, given that Russia then supplied over 40% of Germany’s natural gas.21 As Germany and the EU sought to disentangle that energy dependency and maintain electricity supplies, Germany increased coal-fired generation, yet still closed its last three nuclear reactors. It also built LNG import terminals to bring in natural gas, mainly from Qatar and the United States (Figure 5). In a time of crisis, energy security trumped other goals.

Partly in response to the German experience, the 2024 European Union’s “Draghi” report on the state of the EU’s economy pointed to the high-cost and declining reliability of energy as a major factor in degrading its industrial sector.22 It also re-asserted the importance of a healthy economy and powerful industrial base as vital features of geopolitical and military security.

Figure 5: German LNG Imports

Germany’s policies have demonstrated the trade-offs associated with the pursuit of climate ambitions over economic and geopolitical security. By covering its rural landscape with wind turbines and solar panels, Germany succeeded in only slightly improving its pre-2007 rate of CO2 emissions reductions.24 This effort came at the cost of weakening its industrial base, its overall economy, and its security. Meanwhile, Germany increased geopolitical dependence on America and the Middle East for natural gas, and on China for materials and hardware for “transition” energy machinery, especially wind turbines. Fossil fuels continue to be the primary source of overall energy, required both for industrial processes and to ensure a reliable electric grid. Predictably, Germany’s electricity costs are now some of the highest in the world. Germany’s long, slow decline in primary energy use, in part, signals gains in efficiency, but it mostly came from an unprecedented decline in economic growth over the past couple of decades.

5. When wealthy economies export energy production, they impose environmental impacts on less-wealthy nations.

Global trade is widely viewed as both a natural outcome of how civilisation operates and, on average, a global “good” that can benefit both importer and exporter economically and socially. There are of course non-trivial caveats about “fair trade”, transparencies, tariffs, and the like.

However, the locus of industrial activities, especially energy production and manufacturing, are increasingly important. Environmental impacts of all kinds, and in particular CO2 emissions, require that policymakers in wealthy nations recognise that outsourcing to emerging nations the mining of basic materials, the refining of those materials, and the manufacturing of associated components simply shifts CO2 emissions somewhere else.

More than half the world’s CO2 emissions come from Asian nations, which also produce more than half of the world’s goods.25 Similarly, mining has in recent decades increasingly shifted to emerging economies, many with fragile or often compromised political and social structures. Dependence on imports does not make the world “greener”, it just moves environmental and other impacts elsewhere.

The energy systems of China—and Asian nations more broadly—use all forms of energy, but coal supplies 47% of all primary energy, with oil next at about 26%, and natural gas at about 12%.26 We want our products to be inexpensive, but it is naïve and myopic to ignore the reality that those products are being produced using coal-fired electricity and coal-fuelled manufacturing, transported by diesel burning trucks and ships to stores and front doors.

The same thing applies to mining and processing the metals required to make “green” energy hardware, from solar panels and wind turbines to batteries and EVs. Fossil fuels supply the overwhelming majority of energy to global miners, and mining itself accounts for nearly 40% of global industrial energy use.27 China controls 60%–80%, and in a few cases 100% of supply chains for the minerals used for “transition” machinery, a fact relevant not only to exporting environmental impacts but also amplifying security challenges. (Figure 6) All products and goods are moved into markets on transportation equipment using oil somewhere in the supply chains; overall, petroleum powers over 95% of global transportation.28 When it comes to accounting for CO2 emissions, there is only one atmosphere. Exporting industrial and environmental challenges is not a solution, it is a “shell game.”

Figure 6: Energy Resource Dominance

In principle, developed economies should not reduce energy use or CO2 emissions by “exporting” the challenges somewhere else, while feigning “green” outcomes themselves. It is an understatement to observe that the goal to lower global CO2 emissions is extremely difficult. Indeed, the goal is arguably impossible in time frames that are meaningful for practical policymaking. Asian nations are actively expanding their use of coal. While wealthy Europe and the United States have spent more than two decades and trillions of dollars trying to “transition” from fossil fuels to reduce CO2 emissions, the fact is global emissions have risen, predictably, by 50% over that period.30

6. Government mandates and/or excessive intrusion in markets stifles innovation and options.

While there is a long history of governments picking “winners” and then using financial tools—rewards and punishments—to achieve outcomes, the essence of the challenge with energy subsidies and mandates at scale is that, fundamentally, they amount to unjustified confidence in predictions about the future. There are many cautions about the challenges of forecasting, but the hubris and consequences of trying to do so at society-scales are especially relevant in energy domains. When it comes to forecasts in particular, no one owns the “truth”, we can only seek it.

Advocates of subsidies and mandates claim that they stimulate innovation. There is some truth to the fact that people and businesses “innovate” to avoid or accommodate negative impacts. There is also some truth to the value of government support for foundational research. But there is little to no evidence that policymakers’ and bureaucrats’ guesses about the nature and timing for new classes of technology—the real goal sought—is better than what happens in the marketplace. Indeed, the history of foundational innovations is not correlated with, nor does it arise from, mandates or subsidies, whether the invention of the lithium battery, or the combustion engine, or jet engines, or nuclear fission. Instead, subsidies and mandates tend to lock in yesterday’s technologies.

On the claim that EVs are a “revolutionary” advance, dozens of countries and American states plan to mandate that consumers can only buy EVs, and are deploying massive subsidies for both buyers and businesses in EV supply chains to support such mandates. The latter are intended to make a more expensive product more palatable, which data show consumers are not embracing EVs at the rate imagined.31 Mandates and subsidies also “crowd out” the possibility of achieving stated goals—i.e., reducing oil consumption—with cheaper options available today.

Similarly, in many European countries and American states, policymakers are limiting the portfolio of energy choices through subsidies and mandates. They are picking technology and business winners through top-down policies such as prohibiting new natural gas connections, the closure of nuclear plants, subsidies for solar and wind, the closure of active oil production and exploration, and more. All of these choices entail trade-offs. Critically, all such actions are based on implicit, if not explicit, forecasts—not only about progress with the favoured technologies, especially the availability and cost of critical materials and inputs, but also future energy demand. Since economic growth is the key driver of future energy demand—and derivatively, the scale and diversity of supply needed—it bears noting the poor track record of experts in forecasting. Examples abound, from the future price of oil or copper to something as basic as the near-term GDP growth rate. Not only has the expert consensus been consistently wrong about the rate of growth in the near-term, never mind long-term, but even about whether the GDP will rise or fall. (Figure 7)

Figure 7: Track record of expert forecasts of US GDP

When governments pick energy winners, whether with mandates or subsidies, the result is rarely what was intended, even if the intentions seem necessary or noble. In principle, when it comes to scaling, governments are not equipped, willing, or able to react like markets in adapting to unexpected outcomes and unintended negative impacts. As subsidies and mandates become increasingly pervasive, they both intentionally and unintentionally impact freedoms, not just in what energy choices businesses find sensible, but also personal freedoms ranging from when or if some behaviours are affordable or permitted (e.g., vacation travel), or whether certain products are available at all (e.g., bans on the sale of low-cost combustion vehicles, or natural gas appliances). Fundamentally, government interventions do not change the inherent economics or physics of energy technologies and systems.

III. Science and Technology: Energy supply is anchored in scientific and engineering realities that are bound by the laws of nature.

7. Capturing and delivering energy to society is about inventing, building, and perfecting technologies based on what physics and engineering allow.

Technology is always changing, adapting, and improving. Time and again forecasters across diverse domains, with different biases or aspirations, are found to be either cynically pessimistic or naïvely optimistic. The challenge for policymakers in framing plans to ensure society is properly fuelled distils to one of understanding the realistic existing possibilities, and the timelines for advances in promising new technologies.

We can only build in the near term what we discovered and perfected yesterday. The emergence of new energy-producing technologies derives from advances in foundational knowledge and science, and new understandings of the secrets of nature. Breakthroughs are a measure of future possibilities.

For many decades, numerous pundits claimed the limits to oil supply portended “peak oil.” Yet even when such forecasts were popular, technology developments were already underway to, eventually, change that picture. At the same time, we are witnessing an ongoing, long-run electrification technology trend in replacements for fossil fuels, recently in particular with EVs. In both cases, useful forecasts are based on an understanding of how existing technologies progress, while recognizing the challenge of predicting the impact of new technologies.

Some 70 years ago, geologist M. King Hubbert forecasted the American production of oil would peak in the early 1970s. “Peak Oil” memes proliferated, including for many other essential commodities, and the world witnessed a burgeoning “limits to growth” movement. The politically motivated, not resource-limited, Arab oil embargo of 1973–74 that triggered a 400% jump in oil prices amplified the peak oil movement and a global policy rush to find alternatives.33

For a while, Hubbert’s forecast appeared validated when American oil production peaked at around 10 million barrels of oil per day in the early 1970s. Then, a confluence of technologies emerged changing the status quo by unlocking access to the massive hydrocarbon resources extant in shale rock, which previously had been considered non-viable.

During the last two decades of the twentieth century, petroleum engineer George Mitchell pioneered and experimented with the extraction techniques of hydraulic fracturing, later combined with horizontal drilling, and eventually succeeding in producing natural gas from the Barnett Shale in north Texas. Continual engineering and operational advances brought costs down and drove a huge growth in production in numerous shale basins. The resulting doubling of American oil and gas production constituted an unprecedented addition to world energy supply both in scale and pace.

The United States has returned, after over a half-century, to become the world’s leading oil producer. The American technological breakthroughs enabling production from vast shale resources reduced and stabilised global oil and natural gas prices, helped lift the United States from the 2009 global recession, reset the geopolitical energy landscape, and continues to bolster the American economy. To be sure, ultimately there are limits to how much today’s technology can extract from shale. But given that only about 10% of the technically recoverable resource has been produced, and a much lower percentage of the total physical resource, we are a long way from exhausting the fundamental supply.34

The engineering reality story is different when it comes to the assertion that EVs for everyday use constitute a simpler, cheaper, and inherently superior “clean, new technology” to replace oil. The label “clean” is mainly associated with CO2 emissions and indeed EVs do not have tailpipe emissions. They do, however, have tires, plastics, electronics, and many other components—including those relating to electrification—that all require the use of hydrocarbons.

The claim that EVs are inherently simpler, and thus soon to be cheaper than combustion vehicles, comes from the observation that an electric motor has only a few moving parts, versus an engine’s hundreds. But that is an incomplete technology narrative. The EV’s battery is an enormous electro-chemical machine with hundreds, even thousands of parts.

Further, building the EV’s two distinctive features, the motor and battery, requires about 500% more specialty metals and minerals that are mined, refined, and transported around the globe using hydrocarbons, as well as more energy-intensive aluminium in the vehicle body to offset the weight of a typically half-ton battery. There is, similarly, a huge increase in critical metals needed to fabricate wind and solar hardware, compared with conventional fossil fuel electricity production.35 (Figure 8) That translates into far more mining, which is not green, regardless of labels and aspirations—and often done in poorer, less regulated countries where human rights violations are all too common.

In a general, batteries have low energy density and are best suited for smaller vehicles. Bigger vehicles need bigger, heavier batteries, making them impractical compared to dense liquid fuels. The extent to which most vehicles continue to use energy-dense hydrocarbon liquids will be determined by the unpredictable possibility of radical breakthroughs in underlying technologies for EVs.

Figure 8: Critical Minerals Use for Energy Machines

We should expect, given recent history, that technological innovation will continue to unlock fossil fuel resources, and with reductions in environmental impacts. Similarly, we can expect innovation to make mining and the production of EVs more cost-effective, with lower impacts. But the primary growth in EVs will be in dense urban environments. China is the outlier with its enormous state subsidies marbled throughout its industrial ecosystem.

Meanwhile, history often shows that increased use of electricity occurs mainly where the nature of electricity enables entirely new kinds of products and services. And there remain significant opportunities for meaningful, though not revolutionary, advances with solar and wind technologies, and more opportunities for greater use. That said, technology principles help us to understand both the trade-offs and likely timelines, the underlying technological and economic benefits of dense liquid fuels, and the dangers of policies that offer a simplistic black-and-white view which forces binary choices based on easily falsifiable claims about rapid changes and “clean” versus “dirty” options.

8. All society-scale energy systems have trade-offs and environmental impacts.

All energy systems require building machines that need materials, land, and capital, as well as political and regulatory permissions. All have spill-over effects that are indirectly related to using the energy machines themselves, such as the alternative uses for the land, or the effects of some pollutant in the future. There are indirect costs associated with such “externalities”. However, quantifying the cost, or locus, of an externality becomes increasingly difficult and less reliable the farther into the future the impact is felt.

The environment—land, water, local air, and atmosphere—is a highly complex interconnected system, and to varying degrees, all means of providing energy for society have environmental impacts and trade-offs. No energy system is “renewable”, because all machines that access, convert, move, and store energy—drilling rigs, dams, mining trucks, wind turbines, solar panels, trains, boats, planes, pipelines, batteries, and beyond—wear out, produce waste, and require replacement and disposal of materials, some of which can be hazardous. Recycling consumes energy, takes time, is limited in terms of useful recovery, and is often more expensive than producing something new. That is why the idea of a “circular economy” with near-perfect recycling is profoundly unrealistic, and even with aggressive recycling, there remains the challenge of new supplies needed to meet net new demands that come with growing economies.

The unprecedented expansion of American shale production came with environmental challenges. Hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) technique requires large volumes of water to be mixed with sand and small amounts of chemicals and injected at high pressure. A byproduct of this process is surface production of high volumes of wastewater—both the injected and natural subsurface formation waters—that needs to be cleaned up and reinjected back into the subsurface. However, water reinjection has caused small earthquakes in some regions, and thus requires careful management and technological advances of its own.

The same is true of solar, wind, hydropower, and grid-scale batteries, all termed “clean” sources of electricity, while coal, natural gas, and nuclear are labelled as “dirty.” Building “clean” machinery requires massive amounts of steel, aluminium, glass, and concrete. (Figure 8)

In addition, these “hidden” environmental trade-offs are amplified not only by the obvious daily cycles of solar and wind, but also by wide seasonal variations. And, as meteorological data show, there are regular extended periods of “droughts” of sun or wind, as happened again in Germany in the fall of 2024. The Germans have a term, “Dunkelflaute”—i.e., “dark wind lull”—to describe when wind speeds collapse for extended periods, resulting in little to no power generation—an expected phenomenon everywhere, but impossible to predict either in time of occurrence or duration. While grid-scale batteries are proposed for addressing variability, the staggering quantity of batteries at country-scale that would be needed entail not just unprecedented costs but also massively expand the upstream environmental mining impacts.

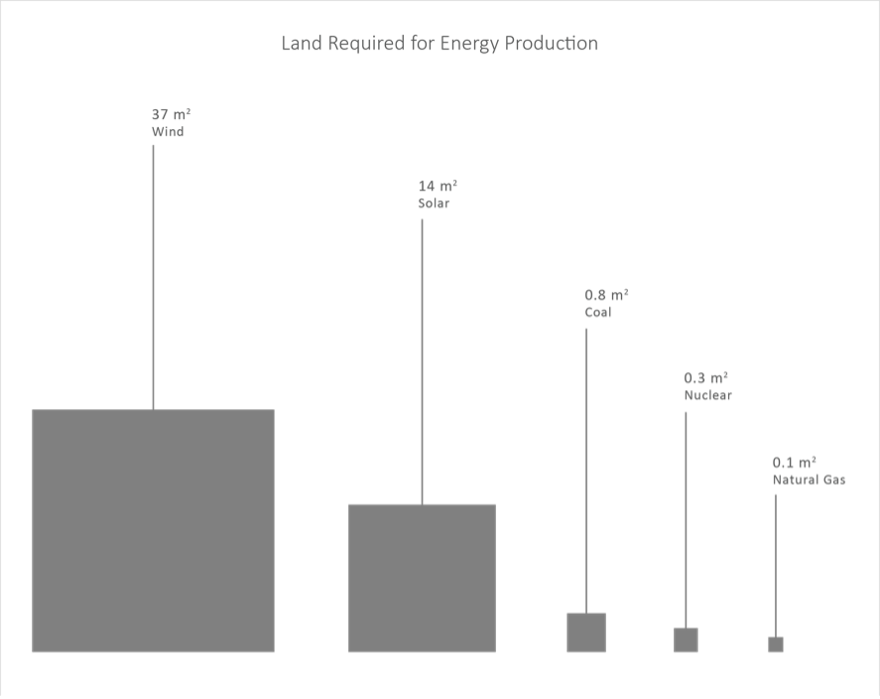

The materials to manufacture “green” machines require “energy minerals” to be transported around the world, especially to-and-from China (Figure 6), which utterly dominates that production supply chain. Importantly, none of the aforementioned considers the enormous increase in land use—over a hundred-fold increase per unit of energy delivered—entailed with deploying “green” machines that are capturing very low energy density inputs from the sun and wind. (Figure 9) Fossil fuels come with their own environmental impacts and risks, not least of which are air pollutants, including sulphur oxides, nitrogen oxides, and particulates, and atmospheric emissions of methane and CO2. Nuclear power requires managing high-level radioactive waste. But, ultimately, when considering the entire range of environmental issues, overall impacts are lessened by using higher, rather than lower, energy density sources.

Figure 9: Land Required for Energy to Power a Single PC Year Round

Interestingly, despite the myriads of environmental issues, climate change dominates public and political discourse. In the scientific community, the essence of that debate is not about whether humanity contributes to atmospheric warming, but the extent and timing of impacts on very long-term weather trends. As to claims that climate change impacts have already emerged as “extreme weather” visible outside of normal variabilities, we can look to the most recent report from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (“IPCC”), recognised as the world’s leading and trusted climate authority. The IPCC clearly summarises data that refutes such claims regarding the weather we experience today. This data includes the absence of evidence for claims of “increasing” or “the worst on record” events such as floods, droughts, fire weather, tropical cyclones, hurricanes, relative sea level, and more.38 The IPCC reminds us that the computer models forecast impacts that could emerge between 2050 and 2100. Why have these IPCC data stayed below the media and policy “radar”?

Environmental impact principles help us recognise and understand the trade-offs with every source of energy. Understanding helps us make wiser decisions to balance the tripartite reality that society needs simultaneously: energy that is affordable, reliable, and that minimises overall environmental impacts. The hyper-focus on just one environmental issue, and the unfortunate invective of the “climate denier” label, are both misplaced. The real impediments to progress are an underlying obliviousness to energy realities and associated denial of trade-offs.

Meanwhile, energy is essential for building the infrastructures and systems that insulate and protect humans from natural predations of all kinds. The most obvious include air conditioning and heating, insulated homes, and weather-protective clothing. Furthermore, the impact on land, materials, and water tends to decrease with denser forms of energy such as hydrocarbons and nuclear, and increase with less dense energy such as wind, solar, biomass, and batteries.

9. The energy available in nature itself is fundamentally unlimited.

The idea of some inevitable “energy transition” is, to a significant extent, rooted in the belief that there are limits to the energy available to civilisation. Delivering useful energy to society is made possible by technologies that can capture natural forces and materials and convert them into a useful form. Forecasting long-term possibilities for energy supplies is thus determined by future innovations that can take advantage of the underlying scale of those primary resources. Scientific estimates of those quantities illuminate the reality that unimaginably enormous amounts of energy exist in the natural world around us.

Earth’s natural fluxes of sunlight, wind, and the movement of water constitute on a daily basis thousands of times more energy than humanity consumes.39 Similarly, the energy existing in estimated global fossil fuel deposits constitutes roughly a thousand years of world energy use.40 Then there’s uranium deposits that hold ten-thousand-fold more energy than global needs.41 Our natural world offers functionally limitless energy supplies awaiting foundational discoveries and revolutionary machines that can usefully harvest and convert it all, some of which may well happen before humanity cracks the code for taming fusion.

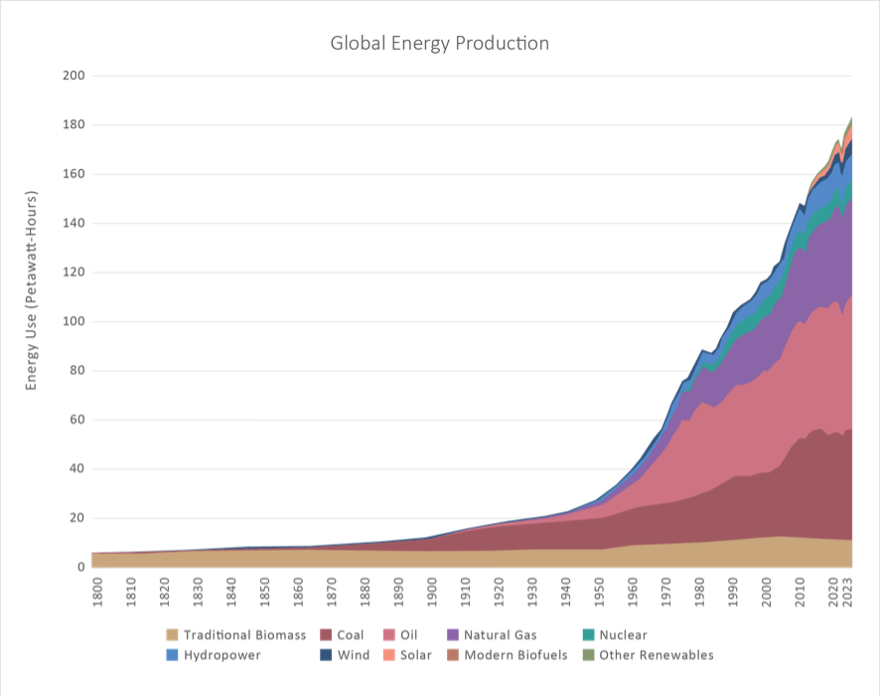

History shows that with progress in knowledge and invention, humanity continually expands the ability to tap into nature’s abundance. And history also shows that the evolution of that progress has always led to expansions of and additions to energy supplies—not a transition away from previous sources. In fact, no source of primary energy—wood, coal, oil, natural gas, uranium, hydropower, solar, wind, geothermal—has yet seen its use decrease, globally. (Figure 10)

The world burns more wood for energy today than 200 years ago. As outlined above, over 80% of global primary energy still comes from fossil fuels—oil, coal, and natural gas. As a practical matter, modern civilisation is anchored in direct and indirect uses of fossil fuels for all products and services somewhere in the myriad and complex supply chains. However, within the mix, coal’s share (%), not its absolute consumption, has been declining, while the share supplied by natural gas has been increasing.

Figure 10: Global Energy Production

The future share of oil and gas supplied to the world will not be constrained by resource limits, only practical barriers based on the technology available for extracting those resources. Technology converts resources into viable “reserves”. Peer-reviewed research of the major American shale basins conducted by the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas found that approximately 500 billion barrels of oil are technically recoverable with today’s technology and at moderate prices, while, to date, only 60 billion have been produced.43

The United States is not the only nation with hydrocarbon-rich shales. Comparable resources exist, for example, in the Middle East, Russia, and Argentina—where numerous companies are preparing, out of the limelight, to bring those resources to market when the economics and timing are right. Even Europe has shale resources; accessing them is a political decision, not a technological one. This is not unlike the permissions required to mine for key metals or any of the resources needed to fabricate wind turbines, solar panels, and batteries. Indeed, the extent to which any primary resource is useful—uranium, moving water, wind, light or heat from the sun—depends on political permissions not just economically viable technologies.

In essence, there are no fossil fuel resource limits per se, at least in time frames meaningful for human affairs. This does not mean fossil fuels will be primary energy sources forever. Ultimately, one can imagine fossil fuel production will decline if available technology is unable to produce economically significant additional output from accessible geological resources. All things have practical limits. If the limits of viable conventional energy resources are reached before the development of viable alternative technologies that are scalable, the result will be tighter supplies and higher prices, which inevitably lowers demand but with severe economic penalties. What history shows is that inventions emerge that unlock capabilities across many energy domains, and lead to additions to available energy, rather than transitions away from existing energy supplies.

Resources inherent in nature are often unlocked by unanticipated discoveries and innovations: the shale revolution a couple of decades ago; the fission reactor and the photoelectric effect, both first instantiated about 75 years ago; the gasoline combustion engine automobile 115 years ago; or kerosene 170 years ago. It is, fundamentally, a fool’s errand for governments to use mandates and subsidies to attempt to create an “energy transition.” Too often, when governments pick “winners” from existing—i.e., yesterday’s—technologies, it is done at best based on aspirations more than physics and economics. The central challenge for policymakers is not one of guessing resource adequacy, but of a realistic understanding of the viability and timelines for the emergence of new technologies that add to and expand the portfolio of options available to humanity, and one of supporting investment in basic research to ensure the discovery of new energy technologies.

Conclusion

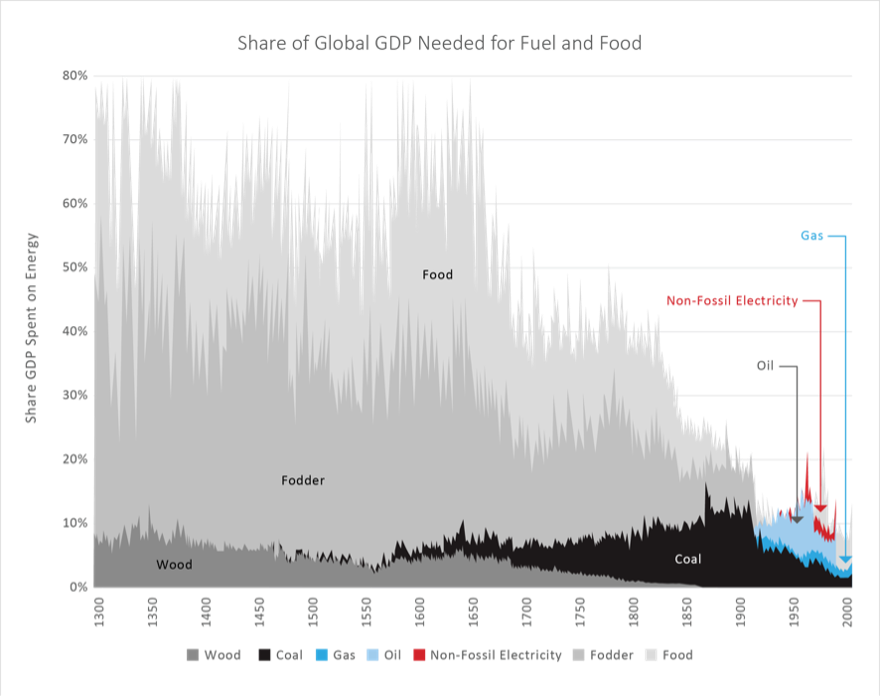

Perhaps the single most remarkable achievement of humanity over the centuries has been the reduction in the share of national economies devoted to simply getting enough food and fuel. For most of history, between 50% and 80% of the economic output of nations has been consumed by those two essential pursuits. Since the dawn of the industrial and fossil fuel era—which are closely interlinked—that share has dropped impressively to below 20%. (Figure 11) This is the real “energy transition”, and it has freed up time and capital for people to spend on education, health, comforts, and protecting the environment.

Figure 11: Share of Global GDP need for fuel and food

The central challenge of our time is thus illuminated by a simple fact that about one-fourth of the world’s population accounts for three-fourths of global GDP. Our goal for the coming century should be to ensure that the whole population—both the less fortunate in already developed countries as well as those in emerging and developing nations—can obtain the material wealth and social conditions enabled by low-cost, abundant energy, and in so doing have the economic wherewithal to invest in environmental protection. That will require significantly more energy.

It is our hope that the nine guiding principles outlined herein offer a framework for policies directed at achieving that goal.

References

- Ekaterina Poleshchuk, “Global Materials Flows Database,” UN environment programme, June 21, 2024, https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/S8_3__Global%20Material%20Flows%20Database_UNEP%20Ekaterina%20Poleshchuk.pdf .

- Energy Institute, “Statistical Review of World Energy,” 2024, https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review

- ibid

- Jason Hickel et al, “Degrowth can work — here’s how science can help,” Nature, December 11, 2022, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-04412-x.

- Scott W. Tinker, “Global Energy, Environment and Economy: Insights for Ecuador,” American-Ecuadorian Chamber of Commerce, Quito, Ecuador, October 2016.

- Our World in Data, “Registered vehicles per 1,000 people,” https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/registered-vehicles-per-1000-people.

- Switch Energy Alliance, “Switch On,” https://switchon.org/films/switch-on/.

- Energy Institute.

- Andrew Reimers, Wesley Cole, Bethany Frew, “The impact of planning reserve margins in long-term planning models of the electricity sector,” Energy Policy, Volume 125, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.10.025: ~15% average reserve margin which totals 190GW (15% of U.S. total grid 1,280 GW). Gas Turbine World, “How much does it cost to build a gas power plant?” July 12, 2024, https://gasturbineworld.com/capital-costs/; ~$1,000/kWh; thus 190 GW @ $1 billion/GW = ~$200 billion.

- Energy Information Administration, www.eia.gov; 4e12 kWh/yr U.S. electricity = 10e9 kWh/day National Renewable Energy Laboratory, “Cost Projects for Utility-Scale Battery Storage: 2023 Update,” June 2023; use 2030 cost of $200/kWh $2 trillion capital cost to store one day U.S. electricity use.

- Tong, D., Farnham, D.J., Duan, L. et al. Geophysical constraints on the reliability of solar and wind power worldwide. Nat Commun 12, 6146 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26355-z.

- Udoy, Md & Mistry, Sunit & Hassan, Abdiaziz & Osei, Frimpong Atta Junior. (2023). Navigating Uncertainty: How Covid-19 is Shaping the Stock Market. European Journal of Business and Management Research. 8. 1-10. 10.24018/ejbmr.2023.8.3.1896.

- Kalghatgi, Gautam. (2021), “Are domestic electricity prices higher in countries with higher installed capacity of wind and solar? (2019 data) J Automotive Safety and Energy, Vol. 11 No. 1, 20210.3969/j.issn.1674-8484.2021.01.008 \.

- Mark P. Mills, “AI May Bring Back Three Mile Island,” Wall Street Journal, October , 2024, https://www.wsj.com/opinion/artificial-intelligence-may-bring-back-th…e-island-microsoft-data-center-energy-c125eef3?mod=opinion_lead_pos7.

- Greenpeace, “Semiconductor industry electricity consumption to more than double by 2030: study,” April 20, 2023, https://www.greenpeace.org/eastasia/press/7930/semiconductor-industry-electricity-consumption-to-more-than-double-by-2030-study/.

- Mills.

- Energy Information Administration, www.eia.gov.

- Energy Institute

- Ibid

- Vaclav Smil, “Germany’s Energiewende, 20 Years Later,” IEEE Spectrum, November 25, 2020, https://spectrum.ieee.org/germanys-energiewende-20-years-later.

- Samantha Gross and Constanze Stelzenmüller, “Europe’s messy Russian gas divorce,” Brookingss, June 18, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/europes-messy-russian-gas-divorce/.

- Mario Draghi, “ The future of European competitiveness,” European Commission, September 2024, https://commission.europa.eu/topics/strengthening-european-competitiveness/eu-competitiveness-looking-ahead_en.

- Global LNG Hub, “The U.S. LNG export boom do not please everyone,”https://globallnghub.com/report-presentation/the-u-s-lng-export-boom-do-not-please-everyone

- Kerstine Appunn, Freja Eriksen, Julian Wettengel, “Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions and energy transition targets,” September 11, 2024, Clean Energy Wire, https://www.cleanenergywire.org/factsheets/germanys-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-climate-targets.

- International Energy Agency, “The changing landscape of global emissions,” https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-in-2023/the-changing-landscape-of-global-emissions

- Energy Institute.

- Tsisilile Igogo, Travis Lowder, Jill Engel-Cox, “Integrating Clean Energy in Mining Operations: Opportunities, Challenges, and Enabling Approach,” National Renewable Energy Laboratory, July 2020, https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy20osti/76156.pdf.

- International Energy Agency, “Energy consumption in transport by fuel in the Net Zero Scenario, 1975-2030,” June 15, 2023, https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/energy-consumption-in-transport-by-fuel-in-the-net-zero-scenario-1975-2030.

- IEA, “The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions,” 2021, https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/executive-summary.

- Statista, “Annual carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions worldwide from 1940 to 2024,” https://www.statista.com/statistics/276629/global-co2-emissions/.

- ACEA, “new car registrations,” December 19, 2024; year-to-date battery-electric sales -5.4%; https://www.acea.auto/pc-registrations/new-car-registrations-1-9-in-november-2024-year-to-date-battery-electric-sales-5-4/

- Philip Hans Franses, Max Welz, “Forecasting Real GDP Growth for Africa” Econometrics 10, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics10010003.

- Michael Corbett, “Oil Shock of 1973-74,” Federal Reserve History, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/oil-shock-of-1973-74.

- David Braziel, “How Much Longer Can Shale Support U.S. Oil And Gas Production?” RBN Energy LLC, July 21, 2023, https://rbnenergy.com/say-youll-be-there-how-much-longer-can-shale-support-us-oil-and-gas-production.

- IEA, “The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions,” 2021, https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/executive-summary.

- Ibid

- David Merrill, “The U.S. Will Need a Lot of Land for a Zero-Carbon Economy,” Bloomberg, June 3, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-energy-land-use-economy/?leadSource=uverify%20wall&sref=lHqvUqWg

- Roger Pielke, “What the IPCC Actually Says About Extreme Weather,” The Honest Broker, July 19, 2023, https://rogerpielkejr.substack.com/p/what-the-ipcc-actually-says-about.

- Vaclav Smil, “Energies,” MIT Press, 1999.

- Ibid.

- IAEA, “World’s Uranium Resources Enough for the Foreseeable Future,” December 2023, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/pressreleases/worlds-uranium-resources-enough-for-the-foreseeable-future-say-nea-and-iaea-in-new-report; ~ 8 million tonnes uranium metal ~ 0.1 EJ per tonne U ~1 million EJ.

- Our World In Data, “Global primary energy consumption by source,” https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-energy-consumption-source.

- Bureau of Economic Geology, University of Texas, “Shale Production and Reserves Study,” 2012, https://www.beg.utexas.edu/research/programs/shale. [1] John & D’Elia Day, et al, “The Energy Pillars of Society: Perverse Interactions of Human Resource Use, the Economy, and Environmental Degradation. BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality, February 2018, 3. DOI:10.1007/s41247-018-0035-6.

~

This research has been produced and published by ARC Research, a not-for-profit company limited by guarantee registered at Companies House with number 14739317, which exists to advance education and promote research.

ISBN: 978-1-916948-44-0 www.arcforum.com February 2025