Energy Delusions: A Critique & Commentary of IEA’s Critical Minerals Outlook

Introduction from the Executive Director of NCEA

The scholars and advisors at the National Center for Energy Analytics (NCEA) are engaged in a mission to help ensure that policies are anchored in reality rather than aspiration because, as the famous writer Philip K. Dick once observed: “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.”

With this report, we turn to the domain of critical minerals, a new area of geopolitical and economic concern that was not on energy policymakers’ radar until recently. It is now well known that goals to rapidly expand electrification and the production of solar panels, wind turbines, and lithium batteries will, by necessity, radically increase the need to mine and refine minerals. The International Energy Agency (IEA), among others, now issues reports about the state and future of critical minerals, with the most recent being the May 2025 IEA Global Critical Minerals Outlook.

A key question now is whether the IEA is providing policymakers with a complete view of reality vis-à-vis these vital materials. To assess that question, we turned for help to two respected experts in mining and minerals: Peter Bryant, who is chairman of Clareo—which advises companies and governments—as well as a member of the NCEA Advisory Board, and his colleague, Satish Rao. Peter and Satish are both deeply knowledgeable in this subject area and advise mining companies and governments around the world. Their candid analysis of the shortcomings of the IEA’s minerals outlook comes at a critical time.

The IEA was created in 1974 at the instigation of the United States in cooperation with 16 nations, motivated by the economically cataclysmic impact of a nearly 400% rise in global oil prices in the wake of the 1973–74 Saudi oil embargo. A founding mission of the IEA was—and still is—to provide policymakers with assessments of the current and likely future state of affairs across energy domains. We doubt any policymaker today would want to see an equivalent energy shock in minerals domains.

It is a truism that the future is hard to predict, but policymakers are poorly served by energy forecasts that are, at best, incomplete. As this report illustrates, the IEA’s assessment about the future of energy minerals is unfortunately lacking.

We hope this critique will motivate the IEA to address the fuller range of threats and opportunities concerning critical minerals, including constructive actions that can be taken around the world to boost security. NCEA and similar organizations stand ready to assist.

Mark P. Mills

Executive Summary:

Critical minerals are more important to the U.S. than ever. They are central to meeting the needs of the demand-driven energy expansion. These materials are so important to the economy that their supply chain is considered a national security priority. However, supply is struggling to keep pace with demand. Headwinds threaten the domestic mining sector’s ability to meet the demand, while the Chinese government aims to win the minerals battle through long-term strategic investments in securing key minerals globally.

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) recent Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025 aims to unpack these challenges and provide forecasts for key energy expansion minerals, including copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, and rare earth elements (REEs). However, our review of the report identified some key missing pieces, the implications of which are described in this paper.

The IEA report neglects to sufficiently identify and analyze the market-shaping activities by countries such as China, which undermine Western investment and operations. This is a massive supply-chain security issue that affects nearly every mineral at different stages of the value chain. The U.S. and other nations remain vulnerable to supply shocks and shortages if they are unable to deploy the tools and create investment conditions to compete with China’s market dominance.

The IEA does not adequately address the mining industry’s struggle to secure and maintain a “social license to operate” (SLO). SLO issues delay or undermine industry attempts to increase the supply of critical minerals. They also lead to broken trust with resource-rich communities and a lack of shared purpose around minerals projects, ultimately undermining prosperity for all stakeholders.

The IEA report neglects to adequately account for ore grade decline and the lack of innovation in critical areas, such as tailings (waste), water, and mining energy usage. Innovation is desperately needed to address these challenges and requires a multi-sector approach.

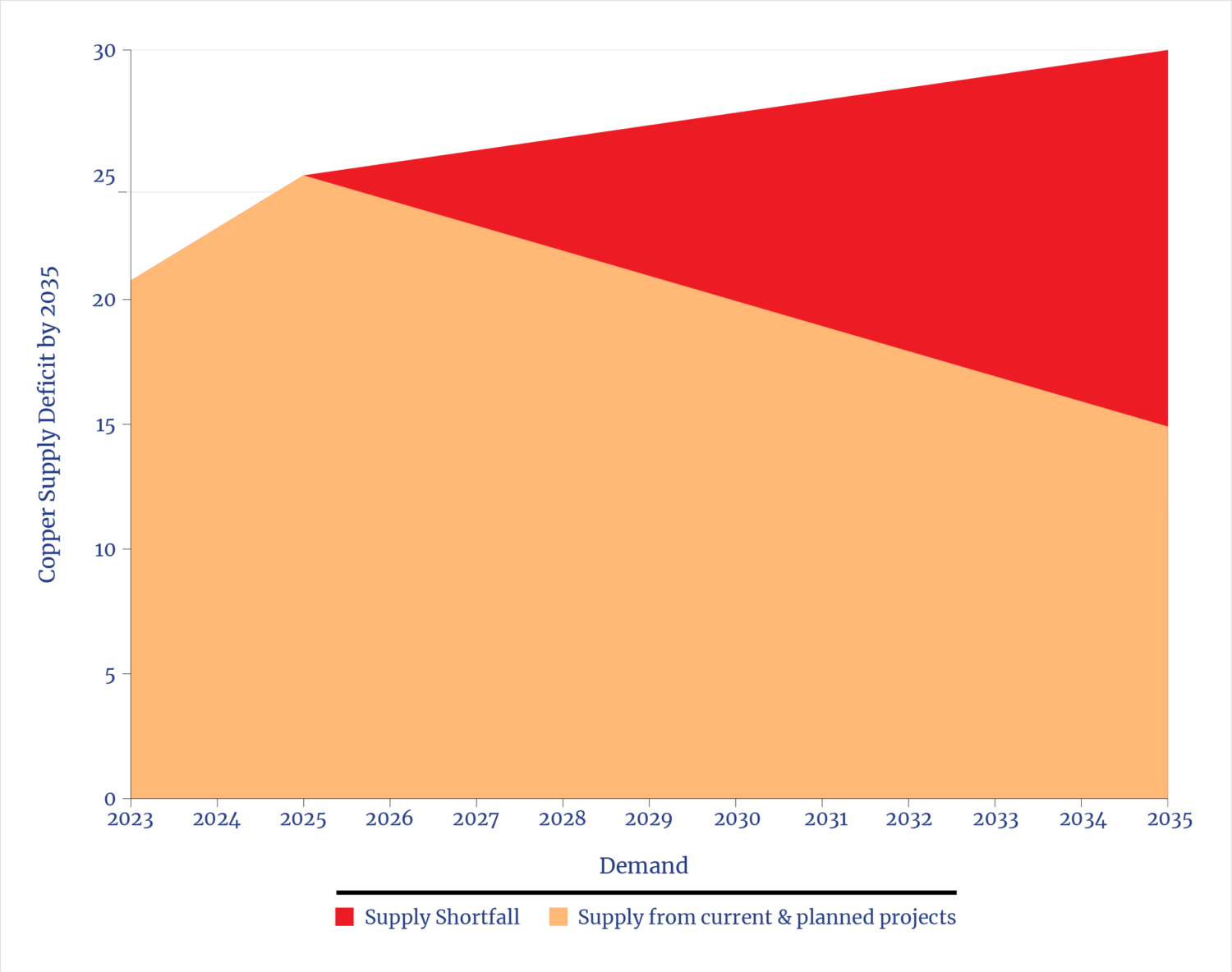

The IEA does not fully explore the implications of projected minerals deficits. This is purely a numbers game, and highly specific to each mineral. While the IEA report does project a 30% shortfall in copper supply, for example (see the graphic on p. 3), the global energy and industrial market disruptions that would occur as a result are insufficiently unpacked. Further, the implications of lithium, nickel, and rare earth shortages are also ignored, despite the serious consequences.

Given the critical level of U.S. minerals dependencies—imports supply 100% of 15 minerals and over 50% for another 32—we recommend four key actions for Congress and the administration:

- Create an integrated minerals policy model

- Establish an interagency framework to advise on triggers for intervention

- Establish a coordinating mechanism for critical minerals

- Create a mining innovation initiative

Copper Supply Deficit by 2035

May 21, 2025, 190

Missing Elements and Flawed Assumptions in the IEA Global Critical Minerals Outlook

In recent years, the IEA has offered important research and perspectives about the state and future of the supply of critical minerals. However, there is a significant gap with the agency’s approach to mineral demands: the agency is not incorporating the realities of the global energy expansion. The IEA is instead prioritizing its models and assumptions based on climate scenarios. The track record shows that the world is not undergoing an energy transition by replacing traditional energy systems with alternatives. Rather, what the data show is a massive expansion in all energy systems fueled not only by economic growth imperatives but also by changes to the sources of demand—notably in electrification and artificial intelligence (AI). The world, in short, continues to depend on a vast fossil fuel-intensive energy system and rapidly expanding energy systems that are far more minerals-intensive. Thus, access to a supply of key minerals is becoming increasingly vital.

The minerals and energy minerals domains are in many ways more complex than the supply chains associated with the traditional energy supply chains for oil and natural gas. While the IEA’s Global Critical Minerals Outlook is an important contribution to the analyses available to policymakers, our careful examination of that report reveals several key flaws in framing and analyzing the vital question of whether future supplies will be sufficient to meet existing trends for higher demands—never mind accelerated demands.

The IEA report neglects to sufficiently analyze the market-shaping activities by countries such as China, which undermine Western investment and operations.

How can companies and governments that operate within a market-based approach compete with a state actor that manipulates markets to collapse prices and affect investment? We’ve seen this play out with many minerals as part of China’s long-term, strategic approach to controlling minerals by choking various points of the supply chain, on a commodity-by-commodity basis. Copper is an example: economies will need dramatically more copper as the pace of electrification continues—and now especially for EVs, solar and wind power. Crucially, there are no viable substitutes for nearly every significant use of copper. Though it is mined globally, more than half of all copper refining is in China. China’s rapid expansion of processing capacity is crushing competition as it is underpricing the market by taking no conversion fees for smelting. Thus, smelters outside China are closing due to a lack of profitability. This will allow China to continue increasing its share of global base metals, as it has been doing steadily for years.

China’s control over a critical mineral such as lithium processing similarly gives it powerful leverage over global pricing, enabling it to flood the market during periods of oversupply, driving down prices so far that it makes it challenging, if not impossible, for Western or allied midstream projects to attract financing.

We have seen similar actions with a variety of other minerals. Indonesia has risen to become the largest producer of nickel, a global base metal. China is investing over $20 billion in that country, and now supplies 55% of nickel concentrate globally. Indonesia recently flooded nickel markets, suppressing nickel prices and resulting in the collapse of the New Caledonian and Australian nickel mining sector. After multiple bankruptcies and closures, BHP’s Nickel West (Australia)—which went into “care and maintenance”—is the most significant example.

China’s dominance of the supply chains of most of the “critical minerals” domain is now recognized as a national security risk. It also has enormous implications for IEA predictions about minerals markets, especially the role of capital markets in these areas.

The IEA does not adequately address the mining industry’s struggle to secure and maintain its social license to operate (SLO).

Opposition to mining projects influences the feasibility and timeline of new projects, both greenfield and expansion of existing sites, everywhere. This opposition is global, including in mining jurisdictions that may have friendlier attitudes toward the industry. This opposition affects minerals ranging from copper and lithium to rare earth metals. The resistance to mining comes from affected communities, indigenous people, and environmental groups, with concerns ranging from environmental degradation, water scarcity, tailings and other wastes, and safety. A recent report from Global Witness, an international NGO, claimed that critical minerals mining was tied to more than 100 violent incidents per year in the top 10 producing countries.

There are legitimate societal concerns about mining. When they are not properly addressed, these concerns can animate local communities, especially if little to no benefits from the industry accrue to them. In some cases, there is misinformation and strategic manipulation of the opposition, but regardless, the effect on project approvals, deadlines, costs, and overall feasibility is real. This opposition can create uncertainty about investment perspective; it can lead to the abandonment of planned and even active projects. While the mining industry has made significant progress in addressing the SLO issues, very significant challenges remain and, in some places, are increasing.

There are many examples, such as the 2024 and 2025 protests in Serbia against Rio Tinto’s Jadar lithium mine due to concerns over tailings and waste management, with fears of catastrophic water and soil pollution. Based on initial plans, this project would have been, by 2027, Europe’s largest operating lithium mine to secure vital ingredients for its battery supply chains. The Serbian government annulled mining permits in 2022 after months of mass protests. Under pressure from the EU, it reinstated these permits in 2024, which led to an immediate backlash and even wider protests. Community concerns over environmental consequences continued even though Rio Tinto promised to deploy newer technologies, such as dry stacking instead of conventional tailings storage facilities.

The Thacker Pass lithium mine in Nevada has faced years of litigation over land use rights and ecological concerns. With commercial production set to begin in 2028 and major construction currently under way, it continues to face setbacks such as the state reversing some of its water permits that conflicted with holders of senior rights. For years, the mine has been a lightning rod for a growing conflict between conservationists, Native American tribes, ranchers, and mining companies. Similar protests are also seen in Chile, where the mining sector is held in high regard. Indigenous groups protested mine expansions because of concerns about water scarcity, especially in the high Andean regions.

Cobre Panamá is another such example. The Cobre Panamá mine, owned by the Canadian company First Quantum Minerals, debuted in 2019 as one of the world’s largest copper operations. It produced about 330,863 tons of copper in 2023, equivalent to roughly 1.5% of the global copper supply. However, a wave of mass protests over environmental concerns, union-led blockades, and a supreme court ruling that deemed its operating contract unconstitutional forced a full shutdown in November 2023. The effects rippled beyond Panama: the loss of this single project pushed a geopolitically important mine offline in less than five years, at a time when new copper capacity was already scarce and global demand is intensifying. Panama’s GDP contracted sharply, and the country lost nearly 5% of its national output tied to the mine, while global markets felt a tightening in copper availability. The mine remained closed as of July 1, 2025, despite a groundswell of efforts to reopen it.

The International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) reports that over 50% of the supply of critical minerals is on or near indigenous peoples’ lands, and the industry will need to reconcile the need to extract these minerals with respect for the right of indigenous people to have a say in how their lands are used and developed. The effect and implications of both organized and spontaneous community opposition are not sufficiently addressed by the IEA, which mentions sustainability performance and traceability systems, and states that 85% of mining companies disclosed ESG metrics in 2023. These compliance-driven frameworks do little to address mounting opposition and the erosion of the industry’s SLO, a factor that should be central to achieving resilient and diversified critical mineral supply chains.

By ignoring these issues, the IEA creates blind spots in understanding true project risk and sustainability—and thus overestimates the potential of a timely expansion of supply. Without appropriately addressing these issues, many technically and financially viable mining projects may never achieve production. The IEA’s failure to fully integrate this aspect into its 2025 outlook creates a critical blind spot in its analysis of supply, demand, investment, and geopolitical trends.

The IEA report neglects to adequately account for ore grade decline and lack of significant innovation in critical areas such as tailings and other waste, water, and energy usage.

The IEA’s latest Global Critical Minerals Outlook does highlight that declining ore grades are a key reason for a potential 30% shortfall in overall minerals supply by 2035. However, it does not offer a sufficiently comprehensive or realistic analysis of the implications of just how much more rock will need to be moved, crushed, and processed to obtain the same outputs of minerals. The rapidly rising quantity of rock that must be mined and processed will require increased water and energy use, which means increased emissions and waste volumes. These challenges have surfaced as water supply and quality are often stressed in many mining jurisdictions.

Today’s conventional technologies to process increasingly low ore grades will unavoidably result in a higher volume of tailings. A 2023 study forecasted a dramatic increase in mining waste production through to 2050. The impact of this increase is already being felt, evidenced by an increasing rate of catastrophic tailings dam failures, with five or six major incidents reported globally each year since 2000. Triggers include heavy rainfall, seismic activity, poor dam construction and maintenance, and increased storage demand due to lower ore grades. This results in further community opposition, as evidenced by the Xatśūll First Nation’s recently filed injunction to urgently stop Canada’s Mount Polley mine from raising its nearly 20-story tailings dam even higher on its territories.

Many of the implications from declining ore grades, such as increased energy intensity, water use, and tailings risks, are deeply entrenched, with little technological progress over the decades. Compared with 1980, today it takes 16 times the amount of rock extracted to reach one pound of copper, 16 times the energy, and twice the amount of water. The IEA report does not discuss the systemic lack of innovation in tailings management, while optimistically focusing on emerging technologies like AI-based exploration, direct lithium extraction, advanced sorting, and re-mining of tailings. These concepts are still emerging and are in early stages. Realism is needed to assess the actual pace of adoption, what is possible, and whether progress is in fact sufficient to address the broader challenges of economic viability and permitting. The IEA, in general, presents an optimistic view of technological progress in mining while ignoring the structural factors that limit progress in this challenging industry. A more realistic assessment of the limitations and timelines of such technologies is required, one that will help policymakers understand the scale and urgency of these challenges, and the possible consequences regarding supply shortfalls.

The IEA does not fully explore the implications of projected minerals deficits.

The IEA report doesn’t go deep enough into the implications of projected minerals deficits. It does highlight a projected 30% shortfall in copper supply by 2035, but it does not fully explore the implications of this copper deficit and the disruption that it would cause to global energy and industrial markets. The high probability of shortages of lithium, nickel, and rare earth metals is also not adequately addressed. Supply shortfalls of these minerals could have serious consequences, including:

Price volatility and inflation: Copper prices are already at historical highs, and future supply gaps will elevate prices further. While prices for other minerals such as lithium and nickel are off their recent highs from a few years ago, volatility could increase over the 5- to 10-year horizon if the IEA supply gaps are realized, which is probable. This will increase costs and shortages across the materials supply chain for equipment and infrastructure for energy expansion, from solar and wind to grid infrastructure, to electric vehicles. Rising costs for products depending on minerals (especially solar, wind, and battery technologies) could also delay project completions, reduce these projects’ ROI, and decrease consumer affordability, all of which would feed back into slower adoption.

Supply-chain disruption: Supply chains could get disrupted as nations attempt to deal with the disruption through protectionism, such as export controls and national stockpiling. This process is already seen through China’s recent bans on critical minerals exports, the suspension of cobalt exports by the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) that began earlier this year, and Indonesia’s nickel export ban. This increases geopolitical risk in supply chains that were already regionally concentrated. Nations or businesses with less purchasing power would be unable to compete for scarce materials, exacerbating inequities in the global energy system.

Energy expansion at risk: Copper is foundational to all things electrical, as it is essential in everything from transformers to EV batteries to solar and wind power distribution. Understanding and modeling these downstream impacts is critical to developing a realistic timeline and priorities to meet expansion goals for alternative energy systems.

The IEA report does not address these impacts through a scenario-based assessment on how supply constraints might affect its energy goals, nor does it identify mitigation steps for companies, governments, and policymakers. Instead, the IEA analysis reveals linear thinking and an implicitly, if not explicitly, optimistic technocratic view wherein supply deficits are noted, but the consequences are insufficiently modeled or highlighted.

Assessing solutions for mineral shortages is highly specific to each mineral. The supply chains for critical minerals are not monolithic, and each one faces different challenges due to applications, value chains, technological development, risk, geology, and geopolitical context. Consider, for example:

Copper is facing a supply deficit in the future because of growing demand, declining ore grades, difficulty in finding and developing large deposits, long permitting timelines, and community opposition due to environmental and safety concerns.

Lithium, which currently has a robust project pipeline, faces concerns including environmental impacts due to the use of water, the slow adoption of new technologies such as direct lithium extraction, and the continued domination of China in refining. To address the lithium supply gap over the longer term, China is structurally dependent on Africa, a region central to its long-term lithium security goals and maintaining dominance in refining.

REE processing is very complex, energy-intensive, and dominated by China, which controls over 85% of separation capacity and magnet production. Efforts to mitigate that dominance, at scale, will take time.

Nickel’s supply is dominated by Indonesia, with financing and influence from China. Most Indonesian nickel firms operate through a complex network of Indonesian subsidiaries that are ultimately controlled by parent companies in China, often with ties to Chinese state-backed lenders. Chinese entities control about three-quarters of smelting capacity.

The DRC mines over 70% of global cobalt, with most of it processed in China.

The concentration of resources is both a market and trade issue as well as a national security and industrial policy dilemma. This landscape also implies that the desire of the U.S. and the EU for a domestic supply of critical minerals must consider all aspects of the value chain, including a push to improve access to minerals domestically, with appropriate investments in midstream infrastructure (to transport, store, and process minerals after extraction) and refining capacity. A reasonable analysis and forecast would model the consequences of failures to resolve the challenges in a timely fashion, or at all. The IEA report gives short shrift to the very real potential for a shortfall: a minerals famine.

Some Proposed Solutions for the United States

We are entering an age of energy expansion, not transition. But adding far more mineral-based energy systems to complement the existing fossil fuel—intensive energy system creates some nontrivial, even massive risks. Those risks all entail the supply of certain key minerals needed to meet demands. This is true across a range of minerals, including copper, lithium, nickel, and REEs. The geopolitical considerations for energy minerals constitute a “minefield” as challenging as—and, in many cases, more challenging than—oil and gas markets. And these challenges are on track to be amplified by the demonstrable fact that the world, and thus the United States, is on the cusp of a minerals famine, with most policymakers ill-prepared to address this potential crisis.

There is a great opportunity for mining companies, communities, governments, and downstream companies to partner on the challenges, focusing on job creation, infrastructure development, and social and economic development in resource-consuming as well as resource-producing countries. The challenge is in balancing that partnership with supply-chain derisking efforts. Most mining industry executives view the current U.S. approach to minerals development as unattractive for forming partnerships. The U.S. is often seen as slow, uncoordinated, or too prone to forms of “social engineering” when it comes to dealing with the realities on the ground in minerals-producing countries. The U.S. currently depends significantly on foreign sources of minerals, and under any reasonable scenario, it will continue to depend on these sources.

While the IEA necessarily analyzes from a global perspective, its reports and forecasts influence domestic policies everywhere, including in the United States. Positioning minerals investment as a national security and industrial competitiveness strategy is important, as is establishing public-private partnerships that can operate with fewer appropriations, reducing dependence on specific budget cycles. Structuring initiatives as part of multilateral programs can help insulate investments.

Tackling these challenges will require that the U.S. government take a different approach. There are a few key actions we recommend:

Create an Integrated Minerals Policy Model

Current U.S. minerals policy lacks a clear mechanism for determining what level of supply-chain risk is manageable on a commodity-by-commodity basis. Different minerals face different exposures across the value chain, and those vulnerabilities vary when it comes to the severity of consequences. Myopically lumping minerals together and attempting to address challenges simplistically won’t address the unique challenges for each mineral and at the varying levels of U.S. exposure.

Policymakers should consider creating a government entity or empowering an agency to create a model that incorporates risk-tolerance thresholds, strategic end-use dependencies, and the different needs of the resource-owner countries and mining companies. This would give the U.S. a filter through which to prioritize possible interventions based on supply-chain exposure, and it would enable better allocation of public- and private-sector investments; it would also create a more competitive U.S. offering in discussions with resource-rich nations. Currently, the U.S. does not have an objective, data-centric definition of what constitutes a secure supply chain for each of the critical minerals.

Establish an Interagency Framework to Advise on Triggers for Intervention

To guide strategic decision-making across the various tools, minerals, and jurisdictions, the U.S. needs a clear framework for when and how to intervene in critical minerals supply chains. As an example of one approach, the Key Minerals Forum—an informal coalition that informs key congressional committees and agencies about issues in the mining sector—has recently published a Minerals Resilience Framework. It provides a simple set of tools for companies and policymakers to better understand the actions needed to deal with the challenges addressed in this report. This framework provides a simple set of tools for companies and policymakers to better understand the actions needed to address the challenges addressed in this report.

Establish a Coordinating Mechanism for Critical Minerals

Given the importance of critical minerals and the precarious international political and economic situation, the U.S. should establish a coordinating mechanism for minerals that oversees all global partnerships, with participation from both governments and private enterprises. As it stands, more than 17 different U.S. federal agencies and departments touch mining. There is no comprehensive U.S. strategy for critical minerals, or any apparent minimal coordination to focus U.S. government activities. Creating a coordinating mechanism would enhance existing efforts related to global trade and partnership formation.

Create a Mining Innovation Initiative

Similarly, if the U.S. and the EU are serious about securing critical minerals, a hard truth must be acknowledged: the current Western model for minerals is increasingly high-cost, high-regulation, slow-moving, and lacks adequate private capital. This model cannot compete with the financing structures and speed of execution that yielded China’s dominance across most minerals. The mining sector’s persistent underinvestment in innovation, combined with its slowness in adopting and scaling new technologies, has handicapped the industry.

A multi-sector response, combined with government support, is needed to address the innovation challenges, since the magnitude is beyond the mining sector’s sole capacity. Key innovation priorities include, among many others:

- Energy and water-efficient refining

- Accelerate projects through AI-enabled exploration, sensing, and processing technologies

- Reduce water and tailings volumes, e.g., tailings reprocessing and new chemistry to potentially eliminate tailings generation

- Improve recovery rates in existing processes (e.g., copper leaching)

The response will require new models and public-private investment in innovation, not just permitting reform and subsidies. It does not imply lowering the standard for environmental and social performance. Instead, the goal is to out-innovate China. Cost-competitiveness and responsibility are not mutually exclusive, and Western companies must lead with a collaborative push to develop the next generation of mining and processing technologies.

For U.S. policymakers, creating or employing a model that enables a means to determine supply-chain vulnerability on a commodity-by-commodity basis, designating a primary minerals authority within the federal government, taking a different approach to global partnership and trade agreements (particularly sectoral trade agreements), and ramping up strategic investment in mining technology innovation are collectively the key features needed to address the impending minerals famine.

Endnotes

- International Energy Agency (IEA), Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025, May 21, 2025.

- U.S.Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025, fig. 2, “2024 U.S. Net Import Reliance” (March 2025).

- “Critical Mineral Mines Tied to 111 Violent Incidents and Protests on Average a Year,” Global Witness, Nov. 7, 2024.

- Francisco Garcia, “The Battle for the Soul of Serbia,” The New Statesman, Jan. 25, 2025.

- Jeniffer Solis, “State Orders Lithium Mine to Stop Unauthorized Water Pumping, Citing Rancher Dispute,” Nevada Current, June 26, 2025.

- Jeniffer Solis, “Thacker Pass Lithium Mine Clears Most Legal Challenges, Minus a Judge Ordered Waste Rock Review“, Nevada Current, Feb. 7, 2023.

- Gracelin Baskaran and Paula Reynal, “Reviving Cobre Panamá Could Be Strategic to U.S. Minerals Security,” CSIS, Apr. 8, 2025.

- Danielle Martin, “We Cannot Ignore the Tension Between the Need to Mine for Critical Minerals and Respecting Indigenous Peoples’ Rights,” ICMM.com, Aug. 29, 2024.

- Rick K. Valenta et al., “Decarbonisation to Drive Dramatic Increase in Mining Waste–Options for Reduction,” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 190, March 2023.

- Giann Liguid, “Expert: African Lithium Key to China’s Battery Supply Chain Dominance,” Investing News Network, July 1, 2025.

- Hans Nicholas Jong, “US Security Think Tank Warns of China’s Grip over Indonesian Nickel Industry,” Mongabay, Feb. 20, 2025.