Who Pays When Wind Turbines and Solar Panels Wear Out? A Hidden Energy Liability

The Issue

Mark P. Mills

Since all machines eventually wear out, and since certain industries and the associated machinery can occupy vast tracts of land, modern sensibilities often dictate that the owner should decommission the energy facility after the useful operational life span of its hardware and return the land to a reasonable facsimile of its preconstruction state. While some U.S. states have long had some form of decommissioning requirements, the modern idea for many of today’s formal requirements originated about half a century ago.

Back then, policymakers and citizens established standards for restoring land disturbed by coal mining and, separately, for decommissioning nuclear plants at the end of operation. Similarly, oil and gas wells have been subject to formal decommissioning requirements for decades. While the motivation can be either aesthetic- or safety-minded, both constitute variants on environmental sensibilities. Given the possibility that the original owners may not be in existence or be financially viable at the time of decommissioning, requirements generally entail forms of up-front payments, bonds, or similar guarantees to ensure that citizens are not left bearing the responsibility in the future.

Now that wind turbines and solar panels are no longer novel—and now that, largely because of mandates and taxpayer-funded subsidies, there are hundreds of thousands of acres of land occupied by wind and solar hardware—it is reasonable to ask whether the owners of those facilities are subject to decommissioning requirements that are as demanding as those imposed on other major energy-producers.

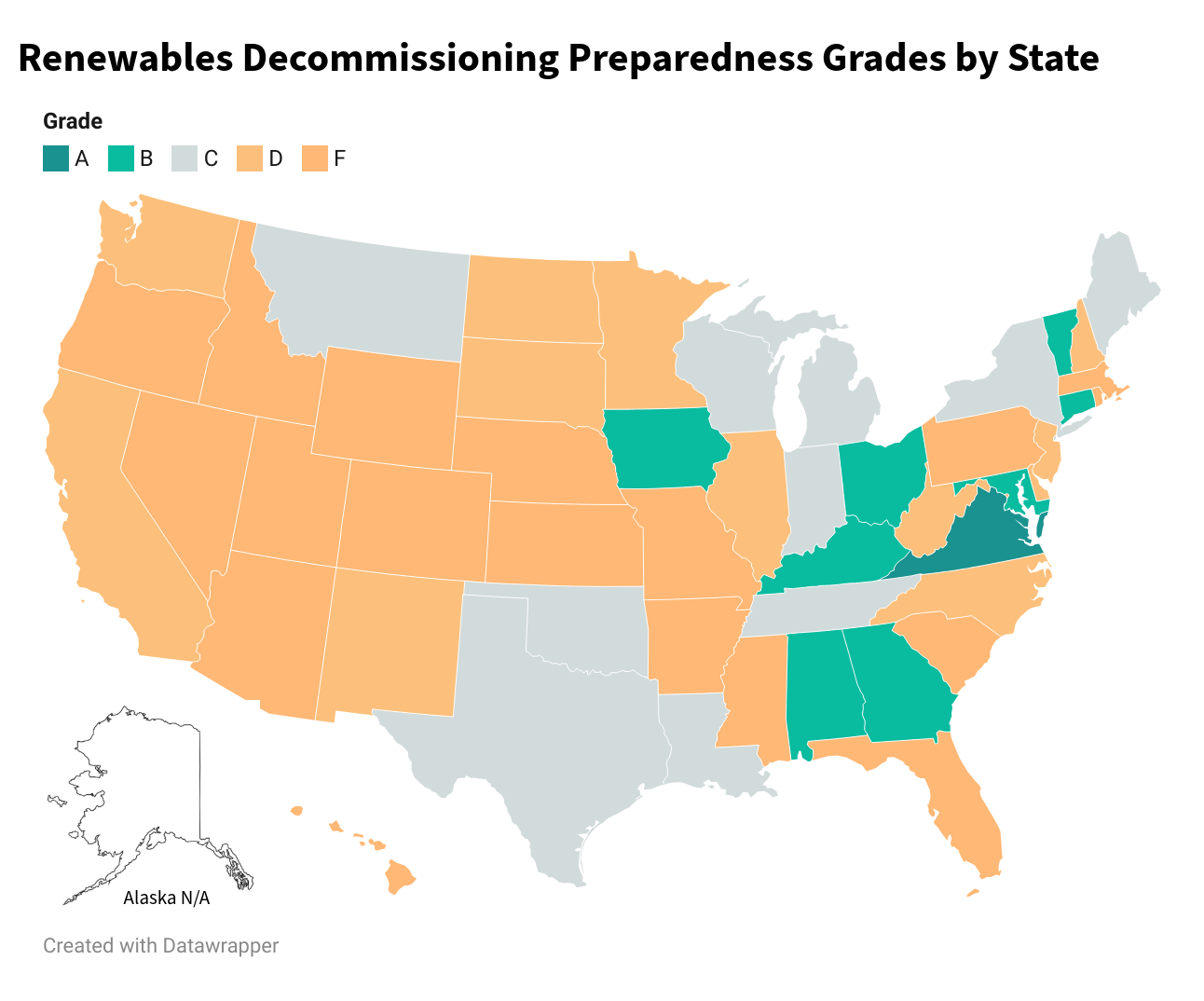

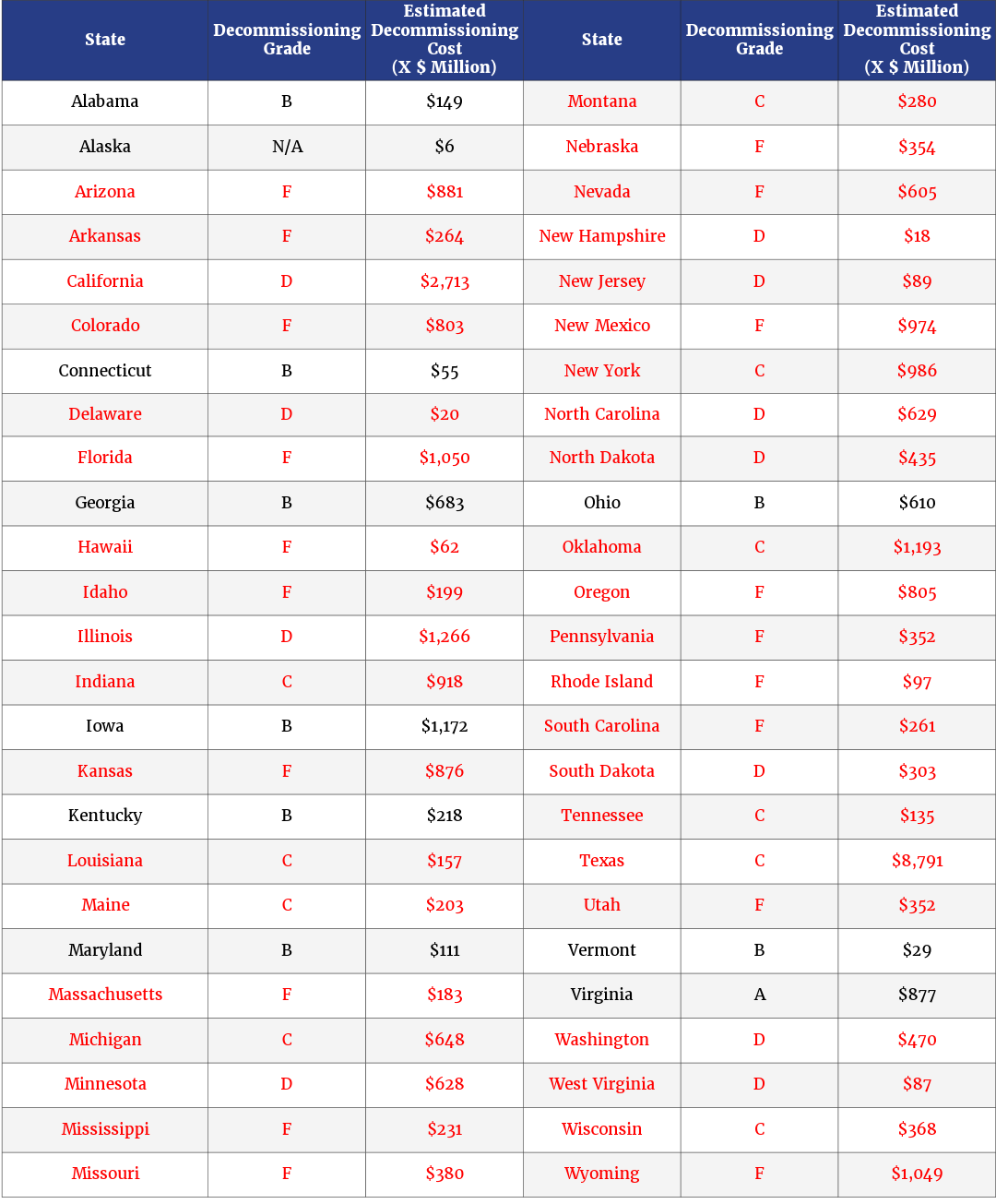

To answer that question, we partnered with Curtis Schube, a lawyer and the executive director of the Council to Modernize Governance. Schube undertook a comprehensive, state-by-state review of the rules and regulations currently on the books for decommissioning wind and solar facilities. For comparison, we asked him to look at similar rules in each state for oil and gas wells, and we asked him to distill the results into a simple grading system from A to F for each state.

We were not surprised at the results. For oil and gas well decommissioning, three-fourths of the 40 states that have oil and gas drilling earned an A or a B, with a full two-thirds earning an A.

Meanwhile, when it comes to wind and solar decommissioning rules, there was just one A grade among the 49 relevant states. Only one-seventh of those states earned a B, with nearly two-thirds receiving a failing grade. This means that consumers or taxpayers—not the owners—will likely be left to pay a significant portion of the $50 billion or more in future decommissioning costs. (We think that the cost estimate, documented in the full report, understates those future expenses; this will be the subject of a future analysis.)

And, given the current debates over massive offshore wind installations, it is relevant to note that Schube, using the same standards, gave the federal government, which has the jurisdiction, a D grade for offshore wind decommissioning, compared with an A for offshore oil and gas well decommissioning.

Read the full detailed and documented analysis of Schube’s work in A State-by-State Assessment of Financial Assurances Required for Decommissioning Wind and Solar Facilities.

The Survey

Curtis Schube

Decommissioning an industrial energy site can be expensive, to the tune of several million dollars per site. For this reason, many states require companies to have financial assurances in place to ensure that the company, or owner, has the funding to decommission at a future time. The alternative would be to risk having the site either orphaned and left in disrepair or leaving the taxpayer to foot the bill.

Ideally, this financial assurance should be in place before construction of the facility commences to ensure that the company doesn’t become insolvent when the structure is in place. Additionally, regulations should use mandatory, non-waivable language; require assurances in amounts sufficient for the task; and mandate that the assurances are in some guaranteed form of negotiable instrument.

Most state jurisdictions appear to recognize the need for regulations that require companies to decommission their end-of-life facilities. The issue is ensuring that the rules are adequate.

We undertook a survey of every state’s rules and regulations pertaining to decommissioning land-based wind and solar facilities and oil and gas wells, and we then rated each state as follows. (Details and citations can be found in the full report.) We sought answers to the following questions:

- Does state law use mandatory terminology, such as “shall,” or discretionary language, such as “may”?

- Does the law fix the amount of financial assurance with certainty, as opposed to giving discretion that could lead to insufficient assurance? Many states articulate something such as “sufficient to cover the cost of decommissioning,” but the idea here is to establish a firm minimum.

- Is the financial assurance of a sufficient amount? Bonds that comprise a small fraction of the cost to decommission do not satisfy this criterion.

- Is the financial assurance guaranteed (i.e., is the financial instrument irrevocable)?

- Is the financial assurance required before the start of a project, or can it be waived or delayed?

Then, based upon the evidence in state statutes or rules for these five factors, we assigned the following grades for each state:

A – All five categories are covered by the regulations.

B – Four categories are covered by the regulations.

C – Three categories are covered by the regulations.

D – The state has regulations but only covers one or two categories.

F – The state should regulate but does not (or effectively does not).

N/A – Regulation is not necessary because the state does not have relevant installations.

The results, summarized in the following table, show a stark contrast. (More detail can be found in the full report.) If calculating the grade point average (GPA) by combining all state scores, the renewable energy financial assurance regulations would have a GPA of just 1.18. Oil and gas well regulations have a GPA of 3.40.

Just one state—Virginia—received an A for renewable energy. Out of the 49 states with relevant facilities, only seven received a B, while 30 states received a failing grade.

Meanwhile, for oil and gas well decommissioning regulation, 40 states have relevant facilities. Of those, 26 states received an A; if B grades are included, the total rises to 31 states.

For comparison, we examined the federal decommissioning rules associated with:

- Nuclear reactors (A)

- Federal lands with onshore wind (C), solar (A), or oil and gas (A)

- Federal lands with offshore wind (D) or oil and gas (A)

Returning to the problematic state of rules regarding onshore wind and solar energy, the fact that many of the facilities are deteriorating more rapidly than originally projected means that significant decommissioning will likely be needed sooner than expected. We would also note that there is a relatively poor level of clarity regarding the eventual amount of decommissioning costs. The uncertainties and variation in estimates are extraordinarily broad. (See Appendix II in the full report.)

Our analysis is not an attempt to determine whether oil and gas or renewable energy technologies are more preferable but rather to examine whether a shared issue—end-of-life decommissioning—is fully understood and properly accommodated.

Grading Decommissioning Preparedness: Summary of Results

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Curtis Schube spent over a decade as an attorney before joining the Council to Modernize Governance, with years of experience in administrative and election law for the state of Missouri. As an Assistant Attorney General, he secured key victories for economic freedom, including defending Tesla’s right to sell cars against entrenched industry interests. He later worked with the Pennsylvania Family Institute on pro-life and religious liberty issues and at the Fairness Center, where he fought to protect public employees from unfair union practices. Curtis also was a senior associate with Dhillon Law Group, where he litigated defamation, Second Amendment, and other constitutional law cases. Now, he is focused on advancing regulatory reform that makes government more efficient, transparent, and fair.

Mark P. Mills is the Executive Director of the National Center for Energy Analytics, a distinguished senior fellow at the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a contributing editor at City Journal, a faculty fellow at Northwestern University’s school of engineering, and co-founding partner in Montrose Lane. His online PragerU videos have been viewed over 10 million times. He is author of The Cloud Revolution: How the Convergence of New Technologies Will Unleash the Next Economic Boom and a Roaring 2020s, (2021). Previous books include Digital Cathedrals: The Information Infrastructure Era, (2020), Work InThe Age Of Robots (2018), and The Bottomless Well, (2005), about which Bill Gates said, “This is the only book I’ve ever seen that really explains energy.” He served as Chairman/CTO of ICx Technologies helping take it public in a 2007 IPO. Mark served in President Reagan’s White House Science Office and, earlier, was an experimental physicist and development engineer in microprocessors and fiber optics, earning several patents. He earned his physics degree from Queen’s University, Canada.