Setting the Record Straight on U.S. Fossil Fuel Subsidies

Listen to the Issue Brief

The Issue

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) signed into law by President Trump in July 2025 cut back on many of the tax credits for wind, solar, and other renewable energy sources contained in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022.1 While these clean energy allowances will take several years to phase down,2 this policy shift has led to renewed calls for leveling the playing field regarding U.S. energy subsidies and, with it, a resurfacing of the exaggerated claims about the level of government financial support enjoyed by the fossil fuel industry.3

Environmental groups and international organizations opposed to traditional energy—coal, oil, and natural gas—have attributed the unrelenting rise in fossil fuels to financial support from governments. Some have taken to tracking subsidy data for the industry, ostensibly to shine a motivating spotlight on the issue. The problem with much of these data is the flawed methodology used to estimate fossil fuel subsidies. Rather than simply measuring budgetary outlays, interpolation is often used—even for the straightforward concept of explicit government subsidies. Some of these data watchdogs have even taken a stab at calculating so-called implicit fossil fuel subsidies—that is, failing to charge companies for the supposed environmental or health costs of their energy generation. This is a theoretical exercise that serves only to cloud the issue and confuse the public.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has monitored fossil fuel subsidies for the past decade and has consistently argued for their removal; it has also been calling for an outright end to fossil fuel investments since 2021.4 In the IEA’s view, fossil fuel subsidies are “inefficient” and “a roadblock on the path to cleaner and more secure energy systems” that is inconsistent with the climate objectives set by the United Nations (UN) at its annual Conference of the Parties (COP).5

At last month’s COP30 gathering in Belém, Brazil, UN Secretary-General António Guterres once again called for the elimination of “fossil fuel subsidies that distort markets and lock us into the past.”6 The International Monetary Fund (IMF), whose mandate is focused on eradicating poverty and promoting economic growth and development, has also weighed in on the topic by compiling its own database for fossil fuel subsidies, which, in the agency’s view, encourage pollution that contributes to climate change and premature deaths.7

The Reality

In the U.S., federal financial interventions and subsidies for the energy sector take four main forms: income tax expenditures for particular corporate and individual taxpayers (e.g., industry-specific expense deductions and tax liability credits); direct expenditures to nonfederal recipients (both producers and consumers) through a grant, loan, or other means of financial assistance; research and development (R&D) support through basic research, leading to the development of new forms of energy supply and improvements to existing technologies; and loan guarantees, mainly from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Loan Programs Office,8 to reduce the cost of borrowing for new clean energy technologies. Of these four categories, income tax expenditures are the main federal subsidy provided to the coal, crude oil, and natural gas industries. In its latest report on the topic, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimated that tax expenditures represented 84% of the total financial support provided to fossil fuels in fiscal year 2022 and 85% over the fiscal 2016–22 period.9

The two main categories of tax expenditures available for fossil fuel producers would include the expensing of intangible drilling costs (IDC) (e.g., labor, surveys, ground clearing, road building, and drainage), which directly reduce the company’s income tax for the year that the costs were incurred, and the use of excess of percentage over cost depletion accounting, both of which function as accelerated depreciation of capital spending for tax reporting purposes.10 Similar expensing treatment for capital expenditures is enjoyed by other industries, including mining, timber, and agriculture.

Other, smaller, energy tax expenditure categories include credits against a company’s tax liability for enhanced oil recovery activities and marginal wells, the deduction of passive losses from oil and gas working interests, the amortization of geological and geophysical expenditures over a two-year schedule, and capital gains (rather than ordinary income) treatment for coal royalties.11 While some of these preferential tax policies for fossil fuels have been in place for many years—in the case of the IDC deduction, since 191312—the amount of aggregate annual revenue loss to the federal government has been minimal over time, given that these are mainly expense-related deductions. Moreover, the inherent volatility of energy commodity prices has made many of these tax deductions reversible over time; in some years, the industry has generated negative tax expenditures (i.e., positive tax revenues) for the U.S. Treasury.

For example, the IDC provision essentially represents a tax deferral. Intangible drilling costs are expensed when they are incurred, resulting in reduced tax revenues for the federal government; however, this up-front loss is offset by tax revenue gains in the following years when no further deductions are allowed. This tax reality is masked by growing oil and gas investments in most years and only tends to come to light when industry capital spending slows sharply due to a weaker commodity price environment.13 This was the case in the wake of the shale-related 2014 collapse of crude oil prices, when domestic drilling activity stalled, and upstream oil and gas assets were aggressively written down by the U.S. industry,14 resulting in the IDC provision and total energy tax expenditures both turning negative over the fiscal 2016–17 period.15

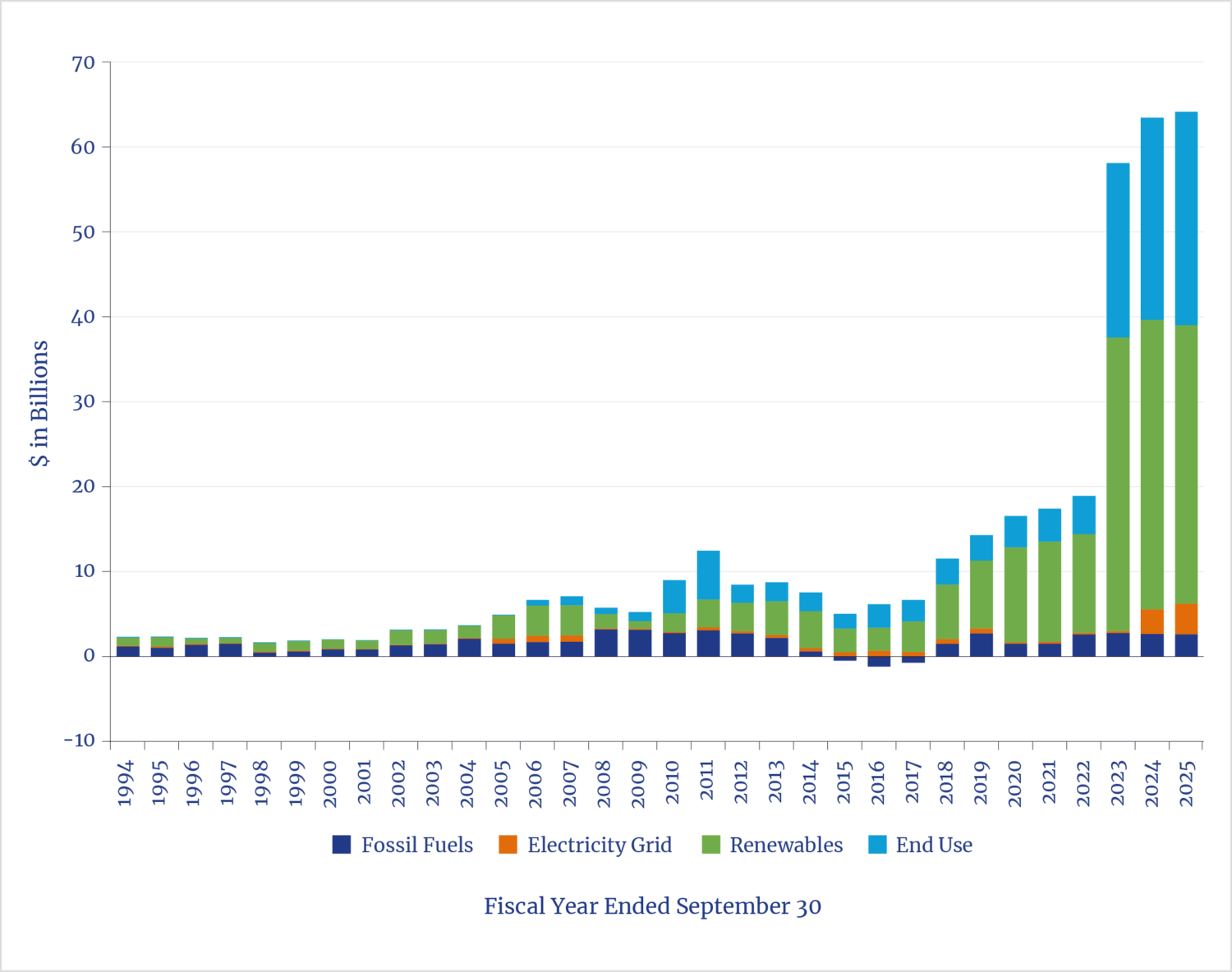

Figure 1 shows the total income tax expenditures for the U.S. energy sector since the mid-1990s, based on estimates prepared annually by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Tax Analysis.16 In fiscal year 2025, fossil fuel–related tax expenditures totaled a net $2.6 billion in revenue losses to the federal government. Over the fiscal 1994–2025 period, the annual average was $1.6 billion. Going forward, the capital spending discipline now ingrained in most American energy corporate suites would seem to imply a continued low level of tax expenditures for the domestic industry.17

Figure 1: Tax Expenditures for the U.S. Energy Sector, FY1994–FY2025

By way of comparison, figure 1 also breaks out the non–fossil fuel component of tax expenditures for the energy industry, highlighting the disproportionate share garnered by renewable developers and clean energy- and efficiency-related end-use projects over the past 10–15 years, particularly the step change in the wake of the IRA’s passage in 2022. In fiscal year 2025, tax expenditures for renewables and end users aggregated $57.9 billion.

Renewable companies mainly benefit from energy production and investment tax credits for wind and solar power projects, as well as various production tax credits for ethanol and other renewable fuels. Unlike the expense deductions primarily used by fossil fuel producers, the production and investment tax credits enjoyed by the clean energy industry can be used to offset the overall tax liability of these corporate filers. Similarly, the end-use category chiefly includes investment tax credits for businesses and individuals who purchase clean vehicles or employ energy-efficient equipment and appliances on their property (both existing and new construction). The amount of federal tax expenditures allocated for renewables and end users in fiscal year 2025 alone surpassed the aggregate total for fossil fuels over the entire fiscal 1994–2025 period ($50.8 billion). Rounding out the industry’s fiscal 2025 tax expenditure total, the electricity grid segment ($3.6 billion) in figure 1 includes production credits and other tax breaks related to nuclear generation, transmission, and utility conservation activities.

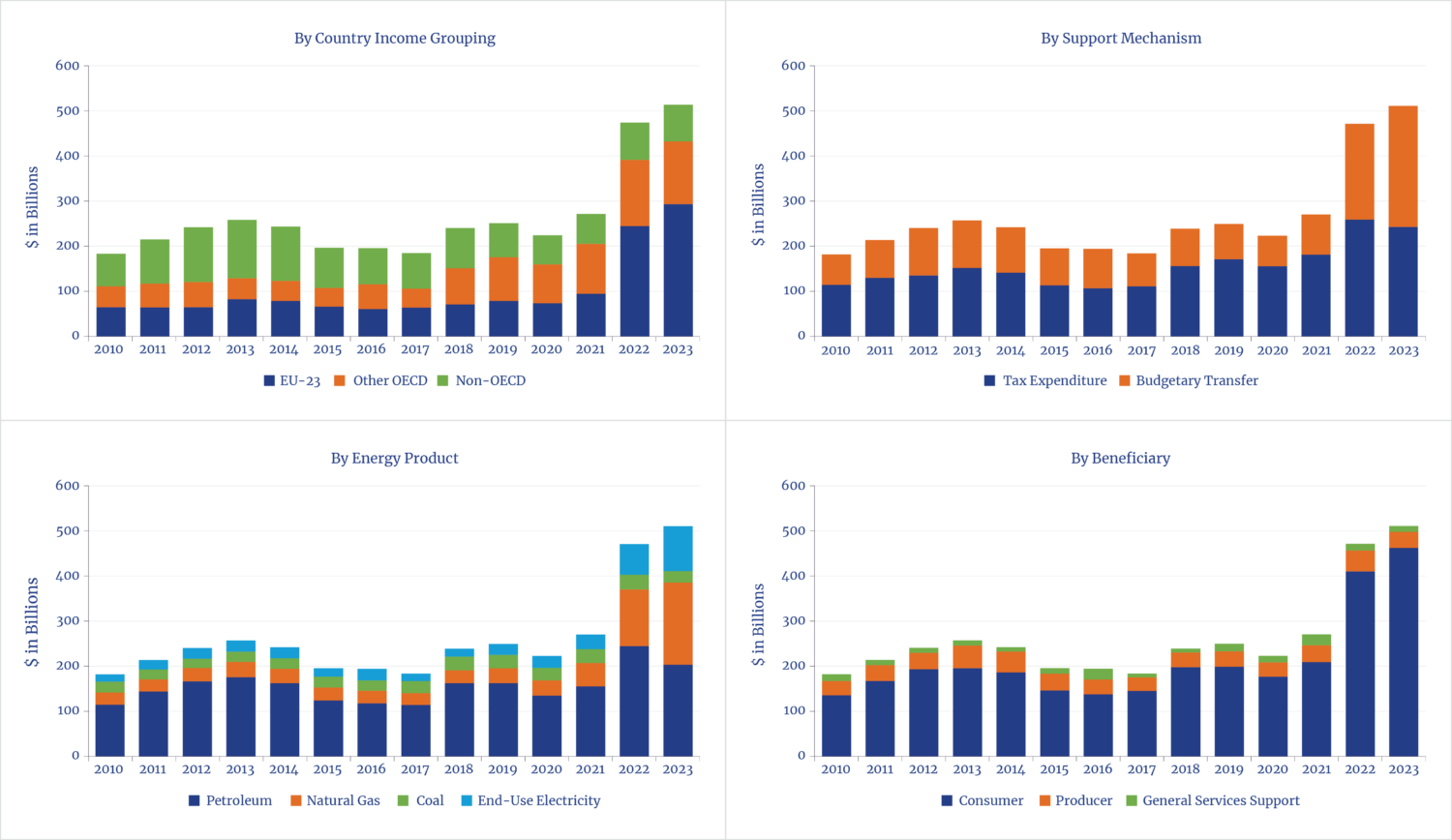

Placed in a global context, the U.S. provides much less financial support to its domestic fossil fuel industry than other nations. Figure 2 shows explicit subsidy data compiled by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD),18 which is derived from government tax and budget records.19 This compares with both the IEA and IMF subsidy databases, which interpolate explicit subsidies from energy prices to calculate undercharging for supply costs, an approach that typically results in overstatement.20 While organized differently, the OECD’s numbers for the U.S. are broadly consistent with the energy subsidy figures of the EIA and the tax expenditure estimates of the U.S. Treasury. This provides a useful frame of reference, despite the OECD’s view that such resources would be better spent on “the transition towards net zero emissions.”21

Figure 2: Global Explicit Fossil Fuel Subsidies, 2010–23

As the four charts in figure 2 highlight, other developed countries—particularly those in Europe—provide significantly more fiscal support for fossil fuels than the U.S., mainly through direct (as opposed to tax) expenditures targeted at the consumer. During 2022–23, total global fossil fuel subsidies more than doubled from the previous run-rate of approximately $225 billion per year over 2010–21. This was due to the sharp spike in global energy commodity prices caused by the outbreak of Russia’s war on Ukraine in February 2022, with the European Union (EU) accounting for almost all the increment. Between 2015 and 2024, European oil and gas production volumes declined by 17% and 24%, respectively.22 This is consistent with the net-zero emissions goals set in the EU’s “European Green Deal”23 and the resulting drop-off in European fossil fuel investment spending over the period,24 which has exposed the continent to energy (especially natural gas) price volatility.25 Europe’s ramping up of fossil fuel subsidies to help consumers pay for fuel and electricity and compensate for the unintended price consequences of its climate policies stands in stark contrast to the U.S. experience. Hydrocarbon supply in this country has not been meaningfully constrained by artificial climate constraints, and energy prices remain comparatively low.

All that said, based on the OECD’s numbers, total fossil fuel subsidies continue to average less than 0.5% of world GDP annually, which is an economic rounding error that has no bearing on worldwide hydrocarbon supply and demand growth. Since the signing of the 2015 Paris Agreement, global fossil fuel production and consumption have both continued to steadily increase despite the best efforts and public promises of signatory countries to force an energy transition away from hydrocarbons. Between 2015 and 2024, worldwide supply and demand for coal, crude oil, and natural gas combined grew by roughly 10%.26 Such industry growth has been particularly dramatic in the U.S., with America now standing as the largest oil and gas producer in the world.27

Lastly, a word on implicit fossil fuel subsidies, given the traction that this chimerical concept continues to have. In 2022, the IMF estimated that implicit subsidies for the global fossil fuel industry totaled $5.7 trillion,28 roughly 12 times the $474 billion of explicit subsidies calculated by the OECD for the same year. The IMF came up with this implicit subsidy figure by using a “baseline assumption that global warming costs are equal to the emissions price needed to meet Paris Agreement temperature goals.”29 Theoretically, it is the sum of all the ancillary environmental and social costs of using fossil fuels that are not being charged back to the industry; it is not a government subsidy, implicit or otherwise.

Besides being highly subjective, the scope of the so-called externalities being factored into the IMF’s implicit fossil fuel subsidies renders these numbers almost meaningless. In 2022, the IMF estimated total fossil fuel subsidies for the U.S. at $757 billion, comprising $3 billion of explicit financial support (which ties to the previously noted Treasury Department analysis) and $754 billion of implicit subsidies. For perspective, the latter figure is roughly equivalent to 3.2% of U.S. GDP and more than twice the nominal GDP of $329 billion generated by the U.S. oil and gas industry in 2022.30

Perspective

In fiscal year 2025, explicit government subsidies in the form of tax expenditures for the U.S. energy sector totaled $64.1 billion, eclipsing those for every other domestic industry. As previously discussed, the lion’s share ($57.9 billion, or 90%) of these energy subsidies flowed to renewables and clean energy users, not to fossil fuels. Repealing all government subsidies (both tax and direct expenditures) for fossil fuel producers would have no meaningful impact on the profitability of the traditional energy industry or, for that matter, domestic demand for hydrocarbons. Most (if not all) of the minimal government financial support currently provided to crude oil, natural gas, and coal companies could easily be eliminated as part of any comprehensive tax reform effort—perhaps in return for an end to the repeated regulatory and legal attacks against the fossil fuel industry, most recently seen during the Biden administration. However, there is no point in discussing the curtailment of total U.S. energy-sector subsidies without addressing their main driver: all the generous tax credits for renewables and clean energy still contained in the Internal Revenue Code. Despite the OBBBA spin, income tax expenditures for renewable energy producers and clean energy users will continue to dwarf those for the traditional energy sector for the foreseeable future, until these climate-related tax perks start to sunset toward the end of the decade.31

Endnotes

- Laurie Abramowitz, David A. Sausen, and Lauren Olaya, “From IRA to OBBBA: A New Era for Clean Energy Tax Credits,” Arnold & Porter, July 22, 2025.

- Alex Muresianu, “How the One Big Beautiful Bill Changes Green Energy Tax Credits,” Tax Foundation, July 31, 2025.

- David Gelles, “Oil, Gas and the Tax Code,” New York Times, October 16, 2025.

- Associated Press, “Energy Agency: End New Fossil Fuel Supply Investments,” NBC News, May 18, 2021.

- International Energy Agency (IEA), “Fossil Fuel Subsidies: Tracking the Impact of Government Support.”

- UN News, “In Brazil, Guterres Calls for ‘Fair, Fast and Final’ Shift to Clean Energy,” November 7, 2025.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF), “Climate Change: Fossil Fuel Subsidies.”

- U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), “Office of Energy Dominance Financing.”

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), “Federal Financial Interventions and Subsidies in Energy in Fiscal Years 2016–2022,” August 2023.

- For tax purposes, U.S. oil and gas producers are allowed to calculate depletion on their hydrocarbon reserves using one of two accounting methods: cost depletion or percentage depletion. Generally, companies must use the method that results in the larger tax deduction (i.e., excess of). Cost depletion allows for the deduction of actual capital expenditures (i.e., tangible drilling costs) for a well in line with the well’s production. By contrast, percentage depletion allows certain producers to deduct a fixed percentage of gross revenue as capital expenses each year, regardless of how much they have invested in a particular well. Current federal tax law allows independent producers (but not integrated companies) to deduct 15% of gross revenue from their oil and gas properties as percentage depletion.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, “Tax Expenditures Fiscal Year 2026: Descriptions of Income Tax Provisions: Energy,” November 27, 2024.

- Will Kenton, “Intangible Drilling Costs (IDC): Tax Benefits and Industry Impact,” Investopedia, November 15, 2025.

- Congressional Research Service, “Energy Tax Policy: Historical Perspectives on and Current Status of Energy Tax Expenditures,” May 2, 2011.

- The Motley Fool, “Oil News: A Flood of Asset Writedowns Looms on the Horizon,” Nasdaq, January 7, 2015.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, “Tax Expenditures Fiscal Year 2018,” September 28, 2016.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, “Tax Expenditures.”

- Sung Je Byun, “Oil and Gas Industry Shows Discipline on Capex, but Risks Remain,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, March 31, 2025.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Data Explorer, “Fossil Fuel Support: Detailed World Indicators.”

- Ibid., “Fossil Fuel Support: Methodology.”

- In 2022, the OECD calculated worldwide explicit fossil fuel subsidies at $474 billion (based on government budgetary records), a figure that compares with interpolated estimates of $1.2 trillion and $1.3 trillion for 2022 by the IEA and IMF, respectively.

- OECD, “Fossil Fuel Support: Key Messages.”

- Energy Institute, “2025 Statistical Review of World Energy.”

- European Commission, “The European Green Deal: Striving to Be the First Climate-Neutral Continent.”

- IEA, “World Energy Investment 2025.”

- Fitch Ratings, “European Energy Price Volatility Within Our Expectations for Utilities,” January 20, 2025.

- Energy Institute, “2025 Statistical Review of World Energy.”

- Scott Disavino and Shariq Khan, “US Oil and Gas Production Hit Record High in December, Says EIA,” Reuters, February 28, 2025.

- Simon Black et al., “IMF Fossil Fuel Subsidies Data: 2023 Update,” IMF Working Paper, August 2023.

- Simon Black, Ian Parry, and Nate Vernon-Lin, “Fossil Fuel Subsidies Surged to Record $7 Trillion,” IMF Blog, August 24, 2023.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Research, “Gross Domestic Product: Oil and Gas Extraction (NAICS Code 211) in the United States,” September 26, 2025.

- National Association of Counties (NACo), “Analysis of Tax Provisions in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” August 27, 2025.